Harold Ancart and Suzan Frecon at David Zwirner

The two shows recently on view at David Zwirner’s Chelsea galleries in New York — by painters Harold Ancart and Suzan Frecon — rest on the dividing line between landscape and abstraction, a liminal space where the affinities of representational and concrete painting become thematically apparent. That these paintings are flat becomes also a sign of their depth, and likewise the tones of color describing the features of distant scenes are elements that adorn the canvas itself. The concept of a picture-plane is embraced in both its meanings; the act of painting is an ambidextrous endeavor.

Thus the two main works in Harold Ancart’s show are aptly called The Mountain and The Sea: two enormous triptychs hung on either wall of a large and narrow room so that you, the viewer, are in fact placed between these two geographies, on an empty strip of land between the hot and arid Mountain and the overflowing Sea. The horizon moves across each panel of both works at a fixed and given height, a flat, consistent boundary delimiting the ground or rather simply marking where one painting’s earth and the other’s ocean meet an endless sky.

Harold Ancart, The Mountain, 2020, David Zwirner.

Harold Ancart, The Sea, 2020, David Zwirner.

The Sea in particular is like an inverted version of Georgia O’Keeffe’s monumental painting, Sky above Clouds IV, which hangs in the Art Institute of Chicago. But the dusty pink and orange tones of The Mountain can also be found on the horizon of O’Keeffe’s Sky. Both O’Keeffe and Ancart’s paintings seem to test the limits of the picture-plane: just how far does the image extend? Visual depth by perspective gives way to the broad expansiveness of the canvas, a wide field across which paint lays and displays its transubstantial effects, transforming from marks made of pigment into a scene and a space that the eye can traverse. The ancestor to both artists in this realm of grand vistas is surely Monet and his masterful Nymphéas panoramas at the Musée de l’Orangerie in Paris.

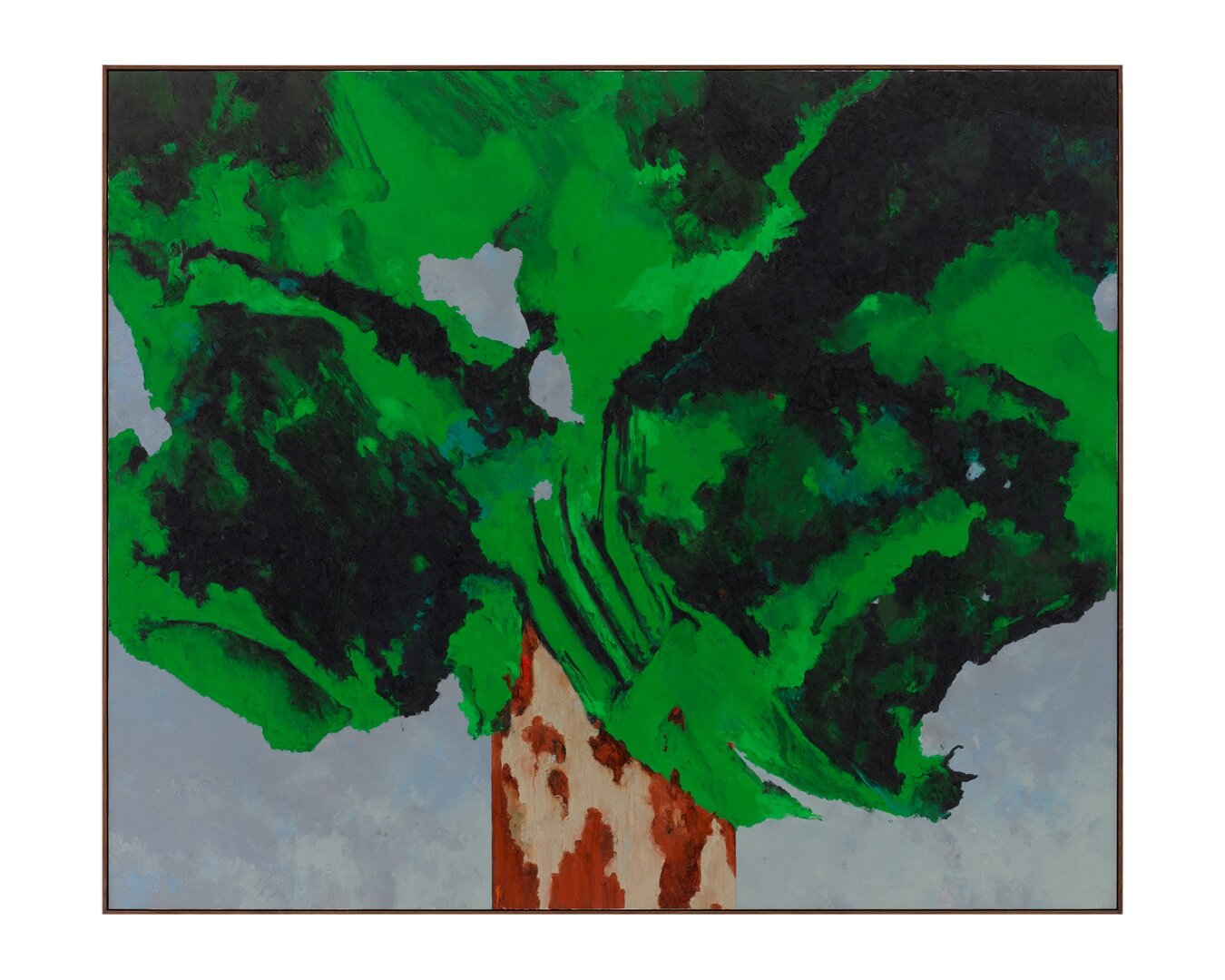

This theme is carried through into the paintings of trees that make up the bulk of Ancart’s show. These, however, are not so successful as The Mountain and The Sea. The artist tells us that they were inspired by the sensation one gets by driving fast through the countryside and looking out the window at columns of trees — the blurred silhouette of the leaves, their bright colors, and the sharp contrast between light and shadow that leaves an impression in passing. But Ancart’s works are too static, like repetitive snapshots arresting a movement whose aesthetic effect only unfolds as a function of continuous time. They are too much the same: close-cropped, round shape, square trunk, flat sky. Only a little dynamism persists in the mark making, but even this detail is heavily muted by a lack of range in the color palette, the shadows too evenly dark and the highlights laid heavy and flatly in only two or three unvarying tones.

Georgia O’Keeffe, Sky Above Clouds IV, 1965, Art Institute of Chicago.

Claude Monet, Les Nymphéas: Matin (left), Soleil couchant (center), Les Nuages (right), 1915-1926, Vogue.

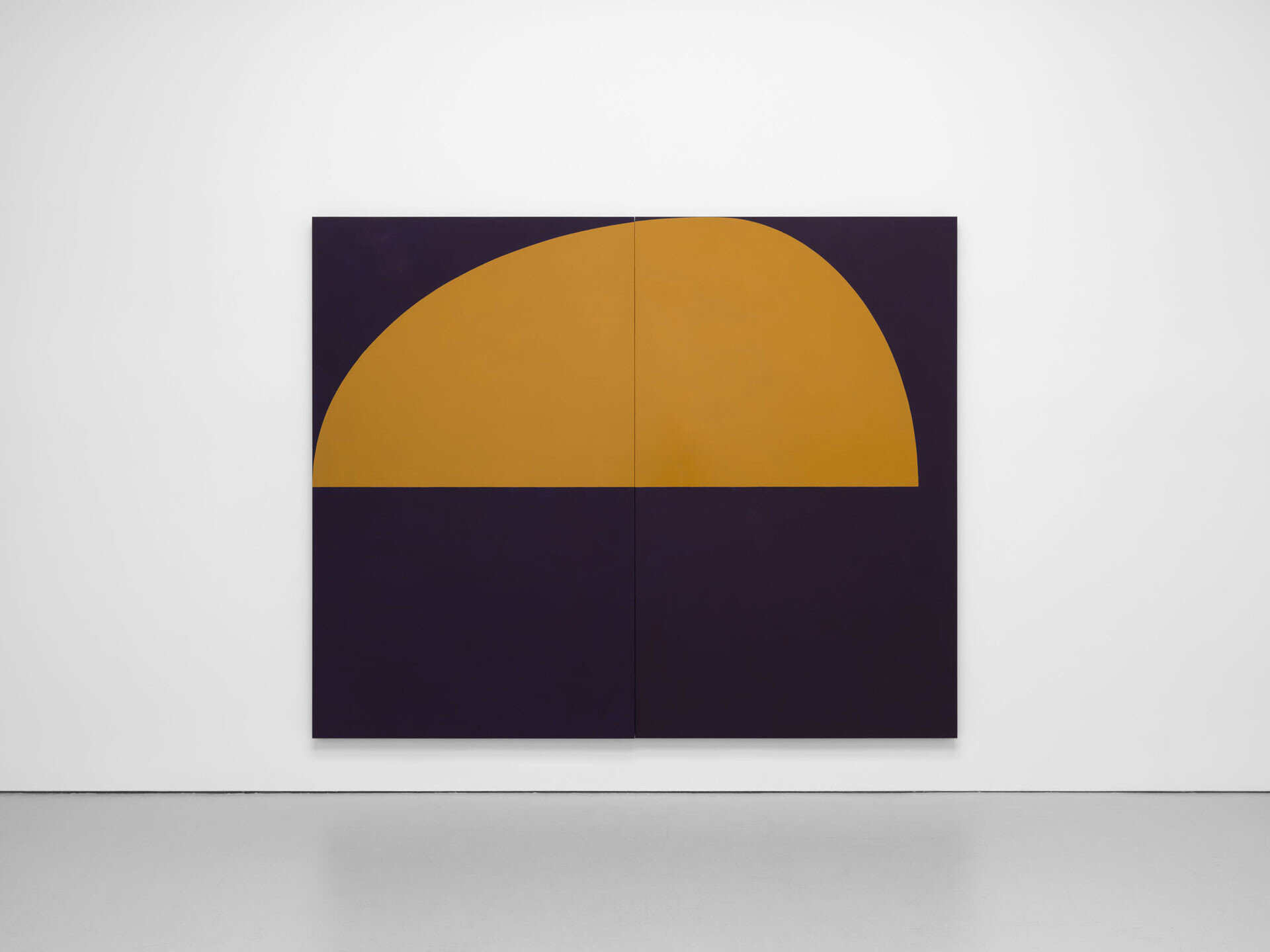

Fortunately, Suzan Frecon’s paintings show us a deeper understanding of color. And an intuitive sense of the shape of an image, of the subtleties of good composition. In their perfect simplicity they also recall some work by O’Keeffe: the paintings of her home in New Mexico where she arranges the opening of her doorway against the terracotta tone of adobe, the flat ground, and a geometric portion of skyspace. Frecon’s paintings, too, are arranged about an opening, a kind of negative space around which the form of each painting emerges. In some, this formation extends upwards, like the moon or the sun rising high in the sky; in others, it’s set back at a distance, like a pond or a lake seen from above; and in still other paintings it operates like the view through an archway or down a hole or a skylight. These are landscapes without landscape — pure ideas of how a picture is painted, of how a landscape is formed as an image. The concept of a picture-plane is embraced in both its meanings; the act of painting is an ambidextrous endeavor: light and dark, near and far, opaque and transparent, empty and full. //

Georgia O'Keeffe, Patio Door with Green Leaf, 1956, Google Arts & Culture.

Suzan Frecon, mars indigo, 2019 (left), Suzan Frecon, siena maria, 2019 (right), David Zwirner.