Anvil and Rose 12

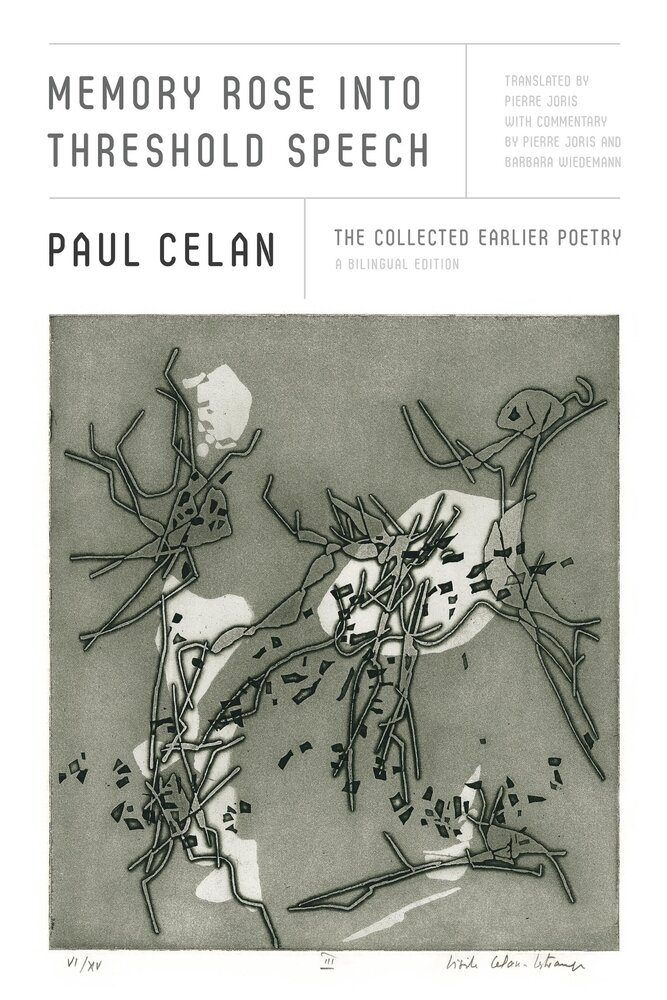

Memory Rose into Threshold Speech: The Collected Earlier Poetry by Paul Celan, tr. Pierre Joris. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2020 ($45.00)

It’s hard to find words to describe the power of Paul Celan’s poetry, its ability to turn language-shards into a kind of prayer for a world that has and continues to tolerate war and genocide. As Celan says in “Psalm,” “NoOne kneads us again of earth and clay, / no one conjures our dust. / Noone.” This volume, with translations of Poppy and Memory, Threshold to Threshold, and Speechgrille, confirms that Celan without doubt was one of the most important poets of the twentieth century. His work shows us that “Everything, / even the heaviest, was / fledged, nothing / held back.” Joris’ translations of Celan bring such a depth of knowledge of Celan’s opus and casts such illumination on his allusions that one can only hope that this book will bring new readers to Celan, as well as attract those who have read Celan in other translations. It’s a dangerous thing to say about any work, but this volume (549 pages) along with Joris’ Breathturn into Timestead: The Collected Later Poetry (736 pages) offer a high tide mark that forthcoming Celan translators will find difficult to match.

Under the Dome: Walks with Paul Celan by Jean Daive, tr. Rosmarie Waldrop. City Lights, 2020 ($15.95)

Think of Gustav Janouch’s Conversations with Kafka, only written by someone with a shower curtain wrapped around his head. In this rather opaque (despite Waldrop’s best efforts) collection of anecdotal jottings, Daive is allegedly translating Celan’s poetry into French. Celan is allegedly translating Daive’s poetry into German. Yet no draft of a translated poem appears in the book, and no in-depth discussion of a poem by Celan or Daive ever occurs. Instead, we observe. Celan is distant, moody, enigmatic: “The world is of glass,” “Being universal, a paving stone can multiply even into hell,” and, charmingly, “My omelet is burned.” Daive engages in dutiful responses and observations: “Your omelet is burned. And you eat it anyway?” But what is up with this anecdote? Daive, “in a Southern city,” writes about a woman he encounters who tells him: “‘Before we part, I want to comb with my golden rake, in front of you watching, the hair on my vulva, my pubic triangle, the model of democracy. Before we part I shall give it to you.’” This reviewer appreciates literary kink as much as the next reviewer, but, Jean Daive, what has this golden rake have to do with Celan, or translation, or the price of a baguette in China?

Twice There Was a Country by Alen Hamza. Cleveland State University Poetry Center, 2020 ($18.00)

“You gave me my tongue,” this poet born in Bosnia-Herzegovina and now living in America tells us. “I give you American-chewed words.” And we are lucky to have these Hamza-chewed words. Sounding at times a bit like Charles Simic and Tomaž Šalamun eating cotton candy at the Fun House (not too shabby poetic godfathers), Hamza gives us our language made strange: “Deep within the pocket of loneliness / lives a feeling whose name is pocket.” Or: “I went to sheets with a new language.” Or: “Passed is passed, but the passing lasts.” At times Hamza’s a trickster, goofing on Pound: “At ten I met—oh lord—you” and “ “The school excursion took us to a kingdom by the sea. I named you Anabel Li.” This poet makes the reader feel pity for those poets who live within the friendly confines of English as their first language and only language. Or to put it another way: Hamza puts most American-born poets to shame (though the inspector can hear some cynics out there saying: “Not that hard to do, Watt.”)

Thresholes by Lara Mimosa Montes. Coffee House Press, 2020 ($16.95)

If you’re going to announce to the reader in your preface “Sylvia Plath ain’t got shit on me” (author’s italics), well, you better be stellar. And that Thresholes ain’t. Instead, we get book-length diary entries, separated by “holes.” That is, small circles, or if you prefer, “thresholes.” The book’s entries vary from the theoretical (“Parentheses outline the places you aren’t”) to diaristic (“The cabdriver wanted to know where to drop me off, but I had no answers, only a heightened awareness that I did not know, I did not belong, and it would soon be dark”). It seems that the “holes” in this book have got the poetry critics wildly excited. In fact, one critic, for The Paris Review, calls it “a language of holes.” Maybe the critic’s referring to the vacuity of the text? I can only respond to this “language of holes” comment with a quote from the book: “Am I guilty now of being post-nostalgic?” My dear Sylvia Plath, if you are listening, please rest easy. You have nothing to fear from this book.

Together in a Sudden Strangeness: America’s Poets Respond to the Pandemic, edited by Alice Quinn. Knopf, 2020 ($27.00)

When the first poem in an anthology states: “What if only poetry will see us through?” (Julia Alvarez), and it’s an anthology of poems on the Covid-19 pandemic, then you know you’re in deep doodoo. Other pearls of pandemic wisdom from this anemic anthology: “Nothing is new” (Eliza Griswold), “While I’ve been writing here, someone over there died” (Peter Cooley), “Forgive yourself for thinking small / for cooking coups, ignoring blight” (Susan Kinsolving), “Mostly, there is nothing to do” (Billy Collins). Maybe this is a book that should only be read by those with good health insurance? Who are in need of bromides? Who are battling the virus of boredom? Who else can endure lines like “To be patient is to be willing / to endure. To forbear.” And: “could ‘we’ / avoid a void // could Ovid / chart the changes.” And: “As I stand in my driveway tonight, / grilling, I feel grateful to the eels.” In other words, write a check for $27.00 and donate it to your local food bank. Then you’re ready for this question from Alvarez: “What if this poem is the vaccine already working inside you?” Thanks, but I’ll pass on the poetry vaccine. Just give me two doses of the real shit.