Anvil and Rose 4

MUSEUM POETICA: ANVIL AND ROSE

The Cipher by Molly Brodak. Pleiades Press, 2020 ($17.95)

This posthumous book of poetry, Brodak’s second, following A Little Middle of the Night, could be titled A Darker Middle of the Night: “We stand on the rim of the void,” “Everything is mostly / nothingness, / they say,” “Fate, // monstrous / and empty,” “Almost nothing isn’t cruel.” And yet there’s an honesty and a courage in these poems, much as in the last poems of Sylvia Plath and Thomas James. Somehow it’s energizing to hear these bleak but honest poems: “Church, morsels, songs, meat, / they just do not love you back. / They just do not.” It’s tempting to say the following lines captures the soul of the book: “The ugly song // a rat teaches her son / so he can sleep.” Yet Brodak’s imagination creates a fierce, stubborn energy: “And wind works / like beauty works, / not attached to what it moves, / beyond matter--, no one makes it, it just sweeps through . . . . ” Brodak will be missed.

Norma Jean Baker of Troy by Anne Carson. New Directions, 2019 ($11.95)

Norma Jean Baker as Helen of Troy. Pop mythology mixes with classical mythology. The perfect blend for a writer with Carson’s background and talent. But something goes very wrong. The Norma Jean sections, in the form of dramatic monologues, have Norma Jean uttering such flat lines as “Oh I need a drink. / Or a big bowl of whipped cream. I’ve got to think.” Not even Norma Jean as Truman Capote can rescue her role, with lines like: “She’s just a bit of grit caught in the world’s need for transcendence.” The best parts of the book by far are Carson’s prose sections, where she focuses on Greeks and their language: “Ancient Greeks gave the name barbaros [barbarian] to anyone not provably or originally a Greek. The word is thought to replicate the sound made by sheep: bar bar bar bar.” So much potential here, but the book fails to live up to its promise. As Norma Jean / Truman Capote would say, “What are we doing here?” If only the barbaric sheep were set loose in the book as a wandering Greek chorus to proclaim: “Bar bar bar bar.”

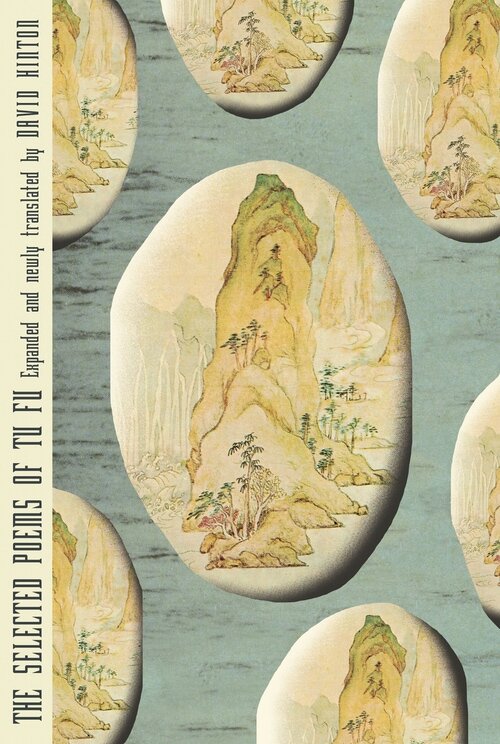

The Selected Poems of Tu Fu: Expanded and Newly Translated tr. David Hinton. New Directions, 2020 ($18.95)

New Directions has long been committed to Asian literature in translation, and it has long ago decided that David Hinton is the one to do it. He has translated many classical Chinese poets, including Wang Wei, Li Po, T’ao Ch’ien, as well as Tu Fu. His earlier “selected poems” of Tu Fu came out in 1989, and now he has revisited those poems, and added more. But this time with a new slant — he claims Tu Fu was deeply influenced by Taoist and Ch’an (Zen) Buddhist teachings. Though Tu Fu has been described by most scholars as deeply influenced by Confucius, Hinton could be on to something. But the translations are the ultimate test. Do the translation work as poems? Here is a line that captures the problem: “you can drift all change on Hundred-Flower Stream.” “All change” is both awkward and unclear. The translator is forcing his interpretation onto the poem. Hinton is best when he conveys specific detail: “the bound chickens thrash around, squawk and shriek.” When comparing Hinton’s translations with Red Pine’s or Gary Snyder’s or J. P. Seaton’s or Sam Hamill’s or Kenneth Rexroth’s, the results become clear. Hinton’s translations feel polished in places but clunky in others: “I nurture Way my own way.” And yet, even a book of uneven translations is worth reading for glimpses of this extraordinary poet, Tu Fu.

Deaf Republic by Ilya Kaminsky. Graywolf Press, 2019 ($16.00)

The critics cannot rave enough about this book: “These poems bestow the power of sacred drama on a secular martyrology,” says the New York Times. “A commitment to poetry as a form of resistance, dialogue, and a noble spiritual vocation,” says Tablet Magazine. Why all the gushing? A.) Deaf Republic’s originality—a book of poems constructed like a novel. B.) The premise: “One morning the country awoke and refused to hear soldiers.” An occupied nation; brutal violence; a brave, non-violent opposition. What’s not to like? C.) Lines like: “Deafness passes through us like a police whistle.” But: A.) the form is not new; there are many poetry-novels. B.) Would this “refusing to hear” the oppressors work in, say, Russia? China? North Korea? Iran? Nigeria? The list could go on. C.) Good lines cannot overcome a cloying premise. It would be nice to believe that “evil” could be destroyed by silence, by this simple act of nonviolent resistance. It feels good to believe this at a time when the U.S. seems to be sliding into authoritarianism. But a book of poetry must be more than a precious conceit and some aesthetically pleasing lines, one would hope.

Wolf Centos BY Simone Muench. Sarabande Books, 2014 ($14.95)

As a note on the title page states, “Centos are a patchwork form that originated around 300 A.D.” The form has gained popularity with The Cento: A Collection of Collage Poems, edited by Theresa Welford (Red Hen Press, 2011). The cento enables Muench to create such lines as: “When the body is cadence of shriveled / memories, do not forget to be animal” and “The heart passing through a tunnel / is a mute creature from whose sleepless / hands the sun has fallen / into a million swallows.” A note in the back indicates that Muench drew from dozens of writers, including Amy Lowell, George Oppen, Meret Oppenheim, Marina Tsvetaeva, James Wright, and C. D. Wright. It makes you wonder what they might say, should these poets be contacted in Poetry Valhalla about finding their work has been sampled without their permission. (The inspector sent several inquiries to the aforementioned deceased, who have not replied as of this date.) Muench’s mantra: “Every transformation is possible.” Whatever it takes to create poems that leap off the page and short circuit the brain of the reader. Wolf Centos achieves that rare state of bringing forth something new under the sun, using the gleanings picked from harvested poetic fields. Yes, that sun that has been around since 300 A.D., but with a recharged heat.