Discipline and Poetics: On Kent Johnson’s “From One Hundred Poems from the Chinese”

In “The Decay of Lying,” Oscar Wilde famously attacks the Romantic celebration of nature, stressing that art is an artifice that stands diametrically opposed to the “natural.” To my mind, this section is one of the most striking in that essay: “Wordsworth went to the lakes, but he was never a lake poet. He found in stones the sermons he had already hidden there.” In other words, while Wordsworth treats nature as a divine, transcendental force that inspires and animates his poetry, Wilde suggests that Wordsworth’s best poetry is little more than an unconscious setting for the poetry that was already within him.

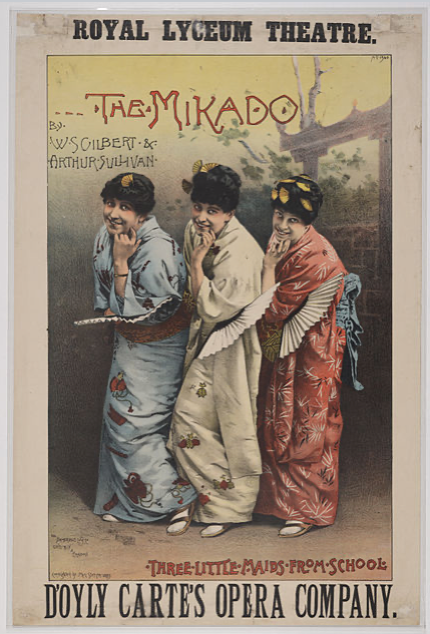

Even before Wilde finished that essay, “Asia” had in many ways replaced nature in European art. From the Japonisme of the Impressionists, to Gilbert and Sullivan’s The Mikado, to the so-called Japanese Village constructed in London in the late nineteenth century, “Asia” in the European imagination was an idealized representation simultaneously ancient and contemporary, familiar and (to use the stereotypical and implicitly racist term) “inscrutable.” As with nature, “Asia” was a construction flexible enough to critique almost any aspect of Western art and/or culture, as writers as diverse as the Imagists, Yeats, the Beats, and many others would later demonstrate.

Since the mid-90s, Kent Johnson has parodically invoked this Western myth of “Asia” to critique the political and aesthetic discipline of Anglophone poetry, as well as its attending careerism and self-promotion. His invention of Araki Yasusada served as a kind of immanent critique of that imaginary construction of Japan: Johnson no doubt knew that Yasusada would be well-received, since that figure perfectly conformed to the Anglophone assumptions about Japan. Yasusada was both contemporary (reading Barthes and Spicer) and comfortably exotic, writing in Japanese poetic forms such as the renga and invoking stereotypical elements such as chrysanthemums. The reception of Yasusada’s work showed the implicit assumptions of Anglophone poetry, especially its obsession with the tragic lives of poets and its patronizing and romanticized celebration of poetic “others.”

Claude Monet, La Japonaise, 1876. MFA Boston

“From One Hundred Poems from the Chinese” in Because of Poetry I Have a Really Big House appears to have begun as a project similar to Yasusada: some of the poems were published in Dispatches from the Poetry Wars under the name Xi Penn. (“Penn” would seem to be a pun on “pen name.”) The title nods toward, or perhaps laughs at Kenneth Rexroth’s collection of the same name, but Johnson’s “China” is not the ahistorical, apolitical, aestheticized dream world that Rexroth invokes. Instead, it is a locus of authoritarian power, as the poem “On Deer Park Slope, I Recall My Old Friend, Wang Chen” suggests. A quick Google search reveals that Wang Chen is a former Deputy Director of the Propaganda Department of the Chinese Communist Party and current member of the Politburo. Wang is no gauzy friend of a long-dead poet, nor is he a figure on a cracked lapis lazuli statue that Yeats owned. Instead, he’s a living instrument of state power. The CCP becomes a hyperbolic (and funny) analog for Official Verse Culture:

Five-toothed toasts and you’re off,

in your wild grad-school style, which hasn’t

changed, even as it never failed to get you in

big-time jams with the poetic Red Guard (41)

It’s fair to say that much of Kent’s work is a kind of ars poetica in which his subject is not just the genre of poetry but the discipline (in the Foucauldian sense) of poetry: who gets rewarded, who gets punished. That’s something that Kent knows quite a bit about. He’s a brilliant poet, translator, and critic, and if he had blunted his attacks on what he calls “the DNC of poetry,” he no doubt could have secured a comfortable academic job at a prestigious university. Of course, if he had done that, he wouldn’t be Kent.

Araki Yasusada (from the cover of Scubadivers and Chrysanthemums)

The Poetry Foundation has been another of Kent’s bêtes noires for some time, and in “Overlooking the Great Tidal Bore at Zhang Ridge with Zhang Qiang” he describes that body’s “labyrinth of State and Corporate passageways” that “branch / for hundreds of miles under the ground” (39). That description could just as easily apply to the Chinese government which, despite being nominally Communist, is in fact a quasi-capitalist dictatorship in which ostensibly private companies are inextricably tied to party leaders and functionaries. While the financial rewards of collaborating with the Chinese government can be very high, the poets who suck up to the Poetry Foundation are sometimes rewarded with little more than the “Literary Buffets of the Imperial Hyatt” (39). Because of poetry, they get a few mini crabcakes and soggy dumplings.

The poems in “From One Hundred Poems from the Chinese” don’t aspire to the brevity and concision of classical Chinese poetry, since they’re relatively long, jumping between themes and styles, and are always very funny. Those stylistic elements suggest something about Kent’s aesthetics: although he’s a former Troskyite, his poetic sensibilities are essentially anarchist in the best sense of the word. He remains deeply skeptical of centers of power at the political and poetic levels, especially since those centers often intersect. Because of Poetry I Have a Really Big House again demonstrates why Kent is one of the most compelling and important voices in Anglophone poetry.

Theatre poster for The Mikado, 1885.