Poetry: George Bowering

Dear Fred Wyatt,

I’m a little confused as to what kind of “intro” you want. I thought I would talk about the poetry but I get the feeling you want this to be a “Let’s All Clap Hands for George Bowering” (headline of a Ubyssey article on George for which we soundly booed him in the cafeteria) sort of thing. I don’t think I could write a legit bio piece on George since he’s spread so much fake news about himself. Don’t you think the audience might already know that he’s famous? I could talk about how fortunate he’s been with women and how he’s ruined all his shirts by putting his fountain pen in his shirt pocket. I think he might have smoked Craven A. I don’t think he learned to skate so he settled for baseball. I thought he was born in Greenwood, the smallest city in Canada, but he says “I was born in Penticton, but I don’t mind it if you say Greenwood because I have left a trail of different birthplaces in various notes on contributors.” The important thing is that he grew up in the Okanagan and can talk hockey about the famous Penticton V’s and the Warwick brothers. He also tells me: “I didn’t smoke Craven As. I learned to skate in Greenwood, but we moved to Oliver and there wasn’t any ice. See chapter one of my hockey book. Dec. 1 is my birthday. Did you forget? My favourite team in Spokane is the Gonzaga dawgs. In Canada we write Okanagan. In the U.S. they write Okanogan.”

Besides baseball, he has an encyclopedic knowledge of Canadian history, particularly western. He has displayed this in a range of novels starting the late 60s. His tongue-in-cheek novel, Burning Water, about George Vancouver’s search for the Northwest Passage won a Governor General’s award. My favourite of his novels is Caprice (1987), a spoofy Western set in the interior of B.C. and his first literary work composed entirely on a computer. Here’s a piece (#31) from my Music at the Heart of Thinking that riffs off of Caprice:

Talking he said like a foreigner would get you snake-eyed commentary or a tongue for booze in fact understand cowboys and Indians as the ones to immolate because that's supposed to be childish sensoryness thinking on the horse or bicycle mind's eye world forever still carving the bows and arrows from vine maple out of the gulley down in Cottonwood Creek all running shoes at the mouth whip stock for slather and the whole earth "noping" some image of themselves one lifetime so Kiyooka says to Bowering twinkle

(TIGHT WORLD, TIGHT LIFE. STREET.

CREEK. BARETT BOYS’ APPLE FIGHTS.

BALL GLOVES WARM FROM SUN.)

He’s written about twenty books of fiction and much of it is what he’s called “biofiction.” His first novel is called Mirror on the Floor and a lot of his life is documented in reflective books. As he says in one of his poems in this issue: “ I cover this paper with my pronoun.”

Although he’s super aware of generic structures and compositional possibilities in all of his writing, and very intentionally plays with them, George performs his acumen for the particularities of “crafting” writing best in poetry. That’s where I first met him, in the University of British Columbia poetry scene in the early 60s. George had gained some campus recognition as a poet, so one night my friend Lionel Kearns and I went up to his rented room just outside the university gates to get him to join us in starting a poetry magazine focused on West Coast poetry. Wisely, Bowering suggested we take the idea to Warren Tallman, our major mentor in the English department. This eventually led to several of us publishing a largely Black Mountain-influenced mimeo mag called TISH which turned out to be “One of the main socio-historical sites for the development of radical poetics in English Canada” (Pauline Butling, Writing in Our Time: 49). Post TISH-era a lot of us from Vancouver moved on, largely to the post-modern institutionalization of creative writing. George bounced around between Canada and Mexico for a few years and then spent an academic life at Simon Fraser University embedded in the Vancouver writing scene (Robin Blaser, Roy Miki, Daphne Marlatt, etc.) and nimbly exercising citizenship in a Canadian literary renaissance (Al Purdy, Margaret Atwood, bpNichol, etc.). You could get a lot of this in Wikipedia or a recent biography (He Speaks Volumes: A Biography of George Bowering by Rebecca Wigod, Vancouver: Talonbooks, 2018).

George has written tons of poetry, both good and bad. His first bad was probably his “Meatgrinder” poems, which our TISH group voted out. His good is widely acknowledged to be Kerrisdale Elegies (1984), a sustained book-length dwelling through Rilke and George’s mid-life in Vancouver’s middle-class Kerrisdale hood. But the range of his poetry (he’s published more books than any poet I know) has always been open, exploratory, and intentionally compositional. That is, it is always interesting from a structural angle as well as from an attentive one.

The batch of poems included in this issue is characterized by Kent Thompson as “totally moving,… late life poems. Totally George, still, in the inimitable cockiness and cool.” That’s it, but they also register an engaging range of response and interaction with both the particular biotext(s) that arise as well as a strong sense of the poem as a field of action for both narrative and rhythm. Probably the primary poetic strength in Bowering’s poetry is the sense of precise rhythm. The poetry in these poems is the bass and drums, the rhythm section. On the page, perhaps, we’re tempted to ferret out the telling, the story. But if the ear really pays attention to phrase, line break, syntactic change-up, it will hear minute and detailed rhythmic shifts in the language. Admittedly, I might be slightly framing my reading of his poetry by having heard him read so often. As my wife Pauline Butling (who knows George as well as I do) says: “When he reads, his hands and index finger move and point through the air as if he was conducting music.” The poem “Basura” is, I think, intriguing proof that he also knows the rhythm section is the “dirt” of poetic language.

…..like a roadside someone threw

basura into, a ditch used up stuff ends down in,

—Fred Wah

Back in the day, when Robert Duncan and Jess Collins were visiting Vancouver, they would spend an hour in Ahren’s bookstore, where I sometimes left my lunch money. Got my Proust there, for instance, some Joyce. Ahren’s always had lots of big, heavy 19th-century books, and that is why Jess went there, because those books had black and white plates in them, and that is what Jess made his famous collages from.

Seems that writers and collage artists like each other’s company, or they even are each other. The only collages I ever made were collaborations with David Young, and I have one somewhere, along with one co-created by David Young and Fielding Dawson. Helen Adam made some of the spookiest collages, while acting in Duncan’s masques and photographing Jess.

Of course, Helen Adam was a friend of Duncan, but not his favourite female writer. That was H.D. (who was hung up on more than one Helen). Through most of our lives, my writer friends and I waited for Duncan to finish writing his immense H.D. Book. He died a little early, and after a reasonable length of time, the University of California published that heavy volume. It was edited by poet Victor Coleman and poet, H.D. scholar and collagist Michael Boughn.

All the things I have said here ought to tell you why I am so happy to have my poems accompanied by Mike’s wide awake colour collages.

—George Bowering

Click enter to win

Michael Boughn

Basura

I’m so happy just be with her’s

a phrase been going around in my head

where the mortality has set up shop,

probably, I don’t know, a normal eventuality,

but when she’s far away from me, I’m awfully

blue. The way blue used to mean, awfully

blue, like a roadside someone threw

basura into, a ditch used up stuff ends down in,

used up being the way old writers

are made to feel. It could happen to you

just as sure as the boat to Hades does not

slow down to let you look at those daffodils,

saying is that too much to ask? You

had your chance to admire the posies; I

told you you walk too fast, and now she

has to slow down just to be with you. If I

could only play my cousin Russell’s saxophone,

I would play all the long slow pieces, waiting

for the bass player to give me a lift up, waiting

for her to end the young brass childhood

of the blues.

Oh!

Michael Boughn

Gilbert Sorrentino

Reading Gilbert Sorrentino on Lorine Niedecker,

I whispered, “It’s nice being here.” Being old

in a chair I decided this moment not to

describe, could be called what we’ve been

waiting for all this time. One keeps changing

one’s mind about poems one has never ceased

admiring, almost, you could say, loving, save that

the remark is reserved for people who never read

anything serious. People sometimes say, oh, I

love your book, and when I have the nerve, I’ll say

that’s not what it was written for.

Rain

Michael Boughn

Running With Luck

When I was a boy beginning sentient life

I could not bear to walk some place, but had to

run, or if the destination was a mile away,

walk fifty steps, run fifty more, my lungs

were one with the Okanagan valley, blood

went gladly where it was bidden. Now when I wake

I begin to learn what parts of my mortal body

will go on hurting this day. There’s something, isn’t there,

wrong with this system, no one told us pain

was coming to fill this joint that offers so much

fun this day, say completing a normal double play,

or say lifting one leg over a cool human July body.

Did we listen to the old folks who smiled their way

and told us we were running with luck, did we

slow down and touch foreheads with them? Did we

imagine that we could fill the spots they would abandon

and take up the issuing of corn-fed adages?

That system calls for gentle acquiescence when you begin

to notice sentience floating away, you say I’ll be

a boy again, just not so much in a hurry to get there.

fragile site, she

Michael Boughn

The Knife

She confused importance with,

he said, sobriety. Her sense of humour

was last seen boarding a mid-sized jet

bound for the second-to-last frontier.

That’s where we’ll focus our search. He

spent his childhood out there, making

driveways out of oyster shells, carving

the initials of a stranger in the skin of

a cherry tree. In her sweet advice to him

she employed the word “mature,” meaning

he should be more, meaning her previous

boyfriend had an English accent. Now she’s

long dead and he’ll be there shortly. There’s

not much more important than that.

Het begint al met

Michael Boughn

Baby’s Breath

First thing in the morning you wake up enough

to shove the poem back down into its container,

vacuous as it may seem, is that where they all

come from, or just the good frightening ones?

That’s why you get coffee into you fast as you can,

to wet the poem, get it into the chute,

back down to where it will never try that again.

Down there where someone you don’t even like

is already thinking of a word to fit into

the word he already has, down there in the dark

where no angel or scholar has ever been seen,

down there where bad luck is the mud you

slide in, a thoroughly heart-breaking place,

unknown to obedient children and your generous auntie,

a home for blind birds at the sea’s bottom on an

unexamined planet smelling of unfortunate innards.

I cannot stress this too much—get out of bed,

look out the window at the cold sunlight, read

the most boring parts of the newspaper.

But

if that poem somehow squirms its way loose

and pants and shivers in your bedroom before

measuring this world—talk sweetly to it, let it

feel the smooth embrace of your body, make it shine

like the moon after a summer rain, send it out

and give it your fondest hope for some life at least.

Propelling Device

Michael Boughn

Could Be

Have I dreamed my life or was it

a true one? Have I chosen or was I

depicted? One moment in Athens

I felt as if I were in a dream, not

dreaming but in such a place. Was it

Athens or a dream of Greece, and who

was dreaming, was I not the dreamer.

I have often said a poem is a moment

of waking up, and then I quit because

I have never liked Plato. My life

could be the title of a book, consideration

as if outside. No, that is impossible.

Let’s start over. The first thing I did,

I mean after being born, was look around

and fall asleep. Or so I’m told

by my fellow dreamers.

Do Dollars

Remember hearing someone say when you were young,

“You can’t take it with you”? And you were probably

being told you ought to spend it while you are here,

or maybe give it to a worthy cause, like

the March of Dimes or Uncle Amos. Don’t be a miser

or a hoarder, especially don’t lay too much value on

mere pelf.

I remember that saying, but

it wasn’t till today, many decades on, not

a lot of them remaining, just this minute thinking:

if you could take it with you, what

would you do with it? Are they going to know

what the hell it is you’re carrying around up there,

or for heaven’s sake, where are you going to

keep it once you get there, and do they do cash

or credit or online banking, and what about

international rates, and are there national things

to make international things, and even if there are,

do they do dollars and pounds and francs and yen

and clam shells and municipal bonds, you see

my problem?

Say you could take some of it with you,

are you going to take pants with you so you can

keep some walking around money in your pockets?

What

Michael Boughn

Hearing and Seeing (and no sestet)

There’s an unearthly silence in West Point Grey,

the dog being home from the vet,

no plastic cone around her neck, no

bang bang thump as she goes through doors,

scratches along the lowest painting, unearthly

silence, reminds you as everything does

that you will be outlived by this dog

no matter how many doctors you go and see.

I Didn’t think I’d see this Again

How can they burn our books

if our books themselves are flames?

Phlogiston, sweet Afton,

will set even you aglow.

How can they undress our words

if our words already speak us naked?

The fire that springs from us now

spoken ten times lovelier

for each water hose they bring to our library,

for every bin load of wet volumes

they haul to their landfill.

When I was a boy, Nazi thugs and Alabama parsons

murdered books. Now publishers themselves,

even knights of the brave poesy houses

turn out the lights over open pages

for fear that a new hire carrying combustible paper

from the far stock room might feel her sensibility

triggered by impolite nouns in 12-point Baskerville,

that their first readers might urinate without intention

on seeing just that terrible pronoun butt its forehead

against the awful weight of their prose.

On Guard

Michael Boughn

I Get You

He gets so excited, it sounds as if

he’s spitting. The delight in growing from boy

to poet, his legs dancing but you can’t see it,

till sometimes his wife mentions calm, and that

is so lovable. Yet spend a night abed in their basement

and you’ll be what’s the word—impressed by the neat

march of bookshelves, they are as still as his conversation

is not. Clothbound science fiction pages have been

turned carefully, like the snake of jazz CDs upstairs,

alphabetical and nice as new. Though I don’t find the wild

men of my saxophone New York heaven bent, still

I see names on that curving shelf and know immediate

respect for his own world. I know he used to spend

his days with people who don’t know the names of his

heros. Yes, I see that, Doug, and I hear what you say—

Look at this! Listen to this! Ah, did you get that?

I can’t even write a careful line about you, I just, I just

want to say, don’t worry, yes, I get you, calm down.

It Would Never Have Been a Sonnet

We old guys sit at our crosswords

in fear of blank spaces joining & spreading

like clouds in our eyeballs, fear

that we won’t for long rise from our chairs

in triumph, hah, we would say,

how many people our age would know

what monarch conquered Assyria?

Right eye closed so we can discern

the little numbers in the squares’ corners,

we stop to imagine being watched

by young relatives and friends who think

we portray something amusing, maybe

instead of fear I should have said dread.

Screws do not need

Michael Boughn

Joyce

You’d think they’d learn a lesson,

might as well put up a sign: “do not

place a finger in here,” right next to

a hole in the wall, behind which 150

watts of raw electricity. I’m telling you

if people were made of fire, they’d

walk into a fireworks barn in

Wisconsin, nibbling on cheese and reading

Joyce Carol Oates. I like driving through

Wisconsin, you can stop for lunch

and encounter no reason to lift

your head and look around. People are

careful in Eau Claire, everyone there

reads the Farmer’s Gazette, they know exactly

how to dress for the weather. I’d love them,

I’d buy everyone juice and Cracker Jack and

wait for the surprise.

I know that Carol Oates is from small town

New York and New Jersey, but she went to university

in Wisconsin.I know that Cracker Jack came from Chicago but it’s

a short hop from there to Eau Claire.

Gorgeous Fall Colors

Michael Boughn

Lund

You know, I think us old guys have it harder with

this summer heat, or as a matter of fact, with

just about everything. But look, this week

I finally got to see Lund, British Columbia,

and it’s funny, you get a hundred miles from Lund

and nobody knows anything about it. So

the end of Highway 101 is pretty much like

the end of my life. But there’s this: in Lund

someone amended the sign proclaiming

the end of Highway 101, so that now it reads

the beginning.

March 16, 2006

The kind of day that makes me wish I were home.

No one in Tucson can direct you honestly and successfully

anywhere. So I spent $53 on cabs, walked for hours and many miles,

took a bus, limped for a while, and the only reason

I found the store for Jean’s beads was that I turned around

and walked exactly opposite to my latest instructions. And

you cannot hail a cab in Tucson. After a couple hours of walking,

I went to a bank with a friendly name, where pretty Delilah

phoned for a taxi, and sure enough, it never came. I walked

another mile in the heat, sore feet, found a posh hotel at last,

after not getting swarmed in a dark underpass, carrying

jacket and shopping bag, got sweet Brittney to call me a cab,

and he came. When I got to my hotel at the airport they told me

I didn’t have my reserved room, for the second time

in fourteen hours. A miserable day. I hope it gets better.

Excess with hanging towel

Michael Boughn

My Thighs

I finally have a house with a panoramic view, how

depressing, the clouds, as Jean said, come right down

to the ocean, the mountains may be powerful, but

rain fills the sky and dilutes the blood in my arteries,

my brain, all hope I ever developed behind my nose.

We call this some kind of seasonal disorder, but no,

we are not looking for order, poets have no business

looking for order. A thief is in jail, what is that to me?

I want a poem to step into, to feel it against my thighs,

I want to ascend mountains, not understand their system.

People tell me they love my poem; that poem was not

looking for love. It wanted to find its place, not in

the anthology but in the moving air around us, we

have no idea what we mean, that’s not our business,

business is a poor thing to pursue, celebrity has been

properly shunted to the discard pile, truth is a trick

yon liars put behind your head where you can’t see it.

I finally have a house on the street where I lived

in a basement, where I fixed cardboard over my high

window, where I first tried to understand poems, where

sunshine was a metaphor the other side of a flat cartoon.

I have learned not to understand, my handwriting

looks more and more like the strands of obliterated matter

oozing outside. I have Venetian blinds and I have seen

Venice, I have struggled in the flood in Venice, I have

seen children trying to understand snowballs in Venice,

I cover this paper with my pronoun, and I pull the blinds,

sending myself tumbling backward in time, outfitted now

with no knowledge, a perfect bell for some bell ringer

fighting Jean for the rope.

Insect Love

Michael Boughn

Not Gorgeous

Nibbling some unnamed grey meat high in the cool sky

over a whole continent in a no-name jet plane

was not the Australia I’d dreamed, not kangaroo,

not wallaby, not gorgeous long blonde limbs wet climbing

out of the pool in Perth. Always single at a table,

I eat lunch and plan what I’ll ask for at dinner,

a citizen of nowhere in mid-ocean just like every

lorn hero I ever wanted, I used to think ain’t this

romantic? Well, no, not till you write it down,

down or up, no one ever explained the difference.

Basketball in Australia sounds good, something like

a good answer to a question she would ask someone else.

That grey meat was thin and tame, easy on

the teeth. The beer wasn’t all that good. I looked around

—William Blake was not in the plane again, or

does it matter how high we are over this normal ground,

too high, it’s true, to see all the extraordinary animals.

Out of sight the Australia I’d dreamed, meat with no name,

the thrill gone under that far downward curve.

Straws

Every time I read a book it reminds me

that I’m going to die. There’s a final chapter

you hope to read, and silently mouth the words

“The End,” then you open another book

fast as you can. When you first heard that

reporters typed “30,” you still expected to

die before then. Lots of people die in the

books you read, they die before the first

chapter and start mysteries, they die just

before the end and provoke observations,

Life is a book, I’ve heard too often to dis-

believe, that’s where central characters

come from. I keep starting to read books

as a way of staying alive. I hardly ever re-

read a book, you live only once, or do you

live every book you read? Or could that be

grasping at straws? Or is that dying over

and over? That’s a kind of life, isn’t it,

all that dying and dying?

When Robin went into that riverside earth,

we threw books and bottles into the ground,

enough for a good long read and another round.

Warning

Michael Boughn

Patiently

I can tell you this individual

was not new to fooling around, he’d

been a knowledgeable virgin till quite

recently.

He could imagine a human life

different from his own, though he was

now a young history student from a

drab village,

thrilled by the sophisticated nitrogen

he was being introduced to—she was

literally nine years older, many wet

beds older,

more cultured by Austro-Hungarian

music in her unconcerned veins, she

saw the glint of surprising future

soul in him

no years of high school marching band

could direct toward that hole in the agriculture,

direct this naive would-be poet with

a tiny library.

What could she give him but

the confidence her tolerant naked torso

would arouse among his friends patiently

awaiting his genius?

Lohengrin’s Fear

Oh, what if, while buried man

rotted quietly away, woman, for her part,

went on to a feminine world in which

she would be rewarded according to

the quality and quantity of dupes

whom she had made work for

the Ideal on this earth?

See facing page

Michael Boughn

Michael Boughn is the author of numerous books of poetry including Cosmographia: A Post-Lucretian Faux Micro-Epic which was shortlisted for the Governor General’s Award for Poetry, and Great Canadian Poems for the Aged, Vol. 1, Illus. Ed.. He and Victor Coleman edited Robert Duncan’s The H.D. Book, and with Kent Johnson he edited and produced the notorious online journal, Dispatches from the Poetry Wars. He lives in Toronto.

A SKÁLD’S GALLERY

George Bowering

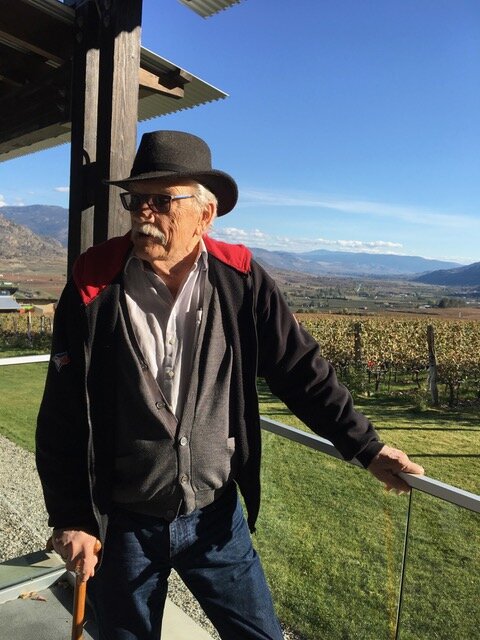

1. Here he is, at a vineyard looking south toward Osoyoos in the Okanagan Valley. A ghost visits home. You'd swear this guy has never been to the big city. I love the look. I expect young PhD students gathering around and asking me to tell them stories about the olden days before they cut down the peach trees and planted grapes. This here is the real west, you effete urban rimesters.

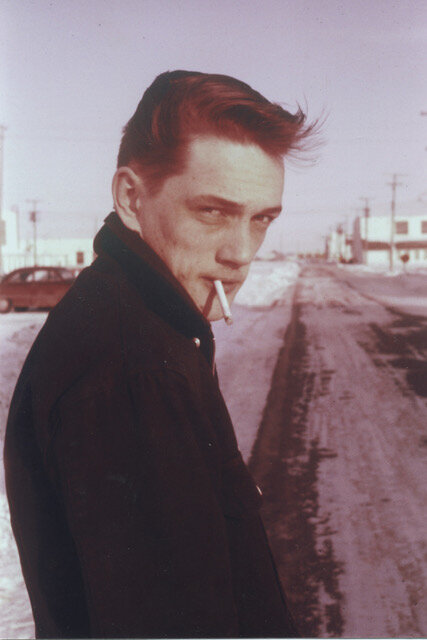

2. Here he is at RCAF station Macdonald, in the melting part of winter in the mid-fifties. In the daytime he serviced the gunsight cameras of T-33 jets. At night he wrote very poor short stories and sent them to unlikely magazines. One day, although he had seen all three James Dean movies, he went to see them all for a second time, two of them in one of the movie theaters in Portage la Prairie and Giant in the other. Nine hours of James Dean in one day. He went around looking like this guy in the picture, until his girlfriend said, "George, you are not James Dean."

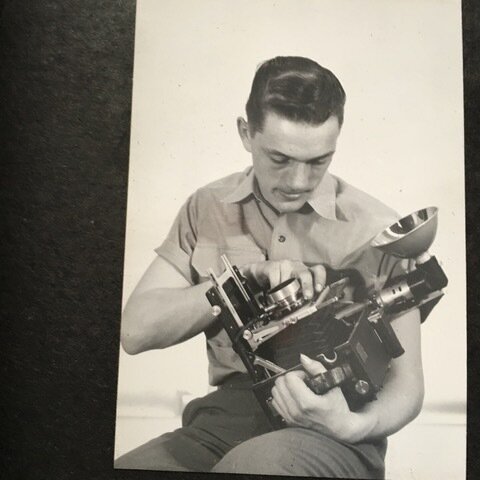

3. In the Royal Canadian Air Force 1954-57 he was officially an aerial photographer but he also got to walk around snowy Manitoba carrying a press camera. He imagined holding up a Speed Graphic at the second Joe Louis - Billy Conn fight. If you walked around the base dangling one of these babies, any NCO on the lookout for volunteer working stiffs would think you were on the job.

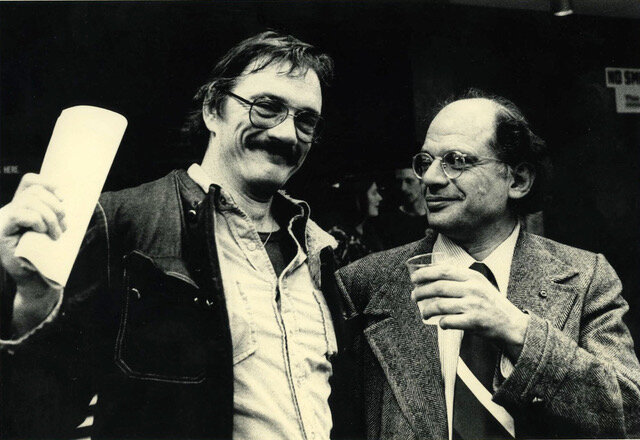

4. Here he joins the four million other poets who had their pictures taken yukking it up with Allen Ginsberg. Allen was the kind of poet who likes to have a drink in his hand and a tie around his neck. They first met when Allen came back from Asia in 1963, taught at the noteworthy UBC poetry summer school, then went by car through George's home town to the U.S. part of the Okanagan Valley. George went to that summer school, expecting to hang around Charles Olson, but felt the aura that emanated from Allen, and followed him around.

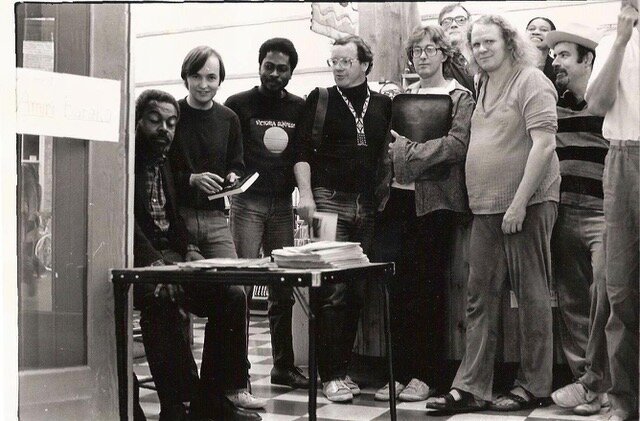

5. Who can remember the year? But the scene was downtown Victoria, where Hope Anderson organized a nice big arts festival where people went nuts for Richie Havens. And then there were all the poets. In one photograph we had Amiri Baraka sitting at a card table, and a lot of people standing up, including John Pass, Hope Anderson, Doug Beardsley, David Phillips, bp Nichol, Billy Little. and behind them, George Bowering and Amina Baraka. And, no, bp was not bigger than everyone else. He just stood out more.

6. He remembers nothing at all about this picture. Apparently it was taken in New Westminster, at a house lived in by Aunty Pam, who was married to Uncle Gerry, a couple who lived in a huge orchard in Naramata. He remembers nothing about the house or the people in it. He remembers nothing about those clothes, though he remembers that nearly every time his mother was going to take a picture of him she would get a tie around his neck. He doesn't remember tossing ties into ditches or fire barrels. He does remember Auntie Pam, though. She was the first woman whose chest he admired, partly. because Uncle Gerry enjoyed it so much.

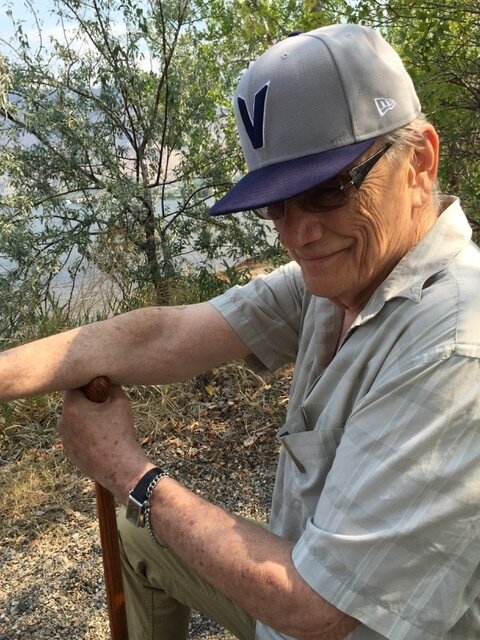

7. In case you're interested, that is a Victoria Harbour Seals cap, but he is wearing it in Osoyoos, in fact on Haynes Point. Haynes Point is a peninsula that reaches almost all the way across Osoyoos Lake. He may be smiling because he is remembering that when they were schoolboys, they promulgated a rumour that Osoyoos girls were promiscuous. Also that they acted loosely with the Yankee guys from Oroville and other towns across the line. Yankee-bait was the term most often heard. Despite all this encouraging news, he left his home town a virgin, and stayed that way until he met a farmer's daughter in Manitoba.

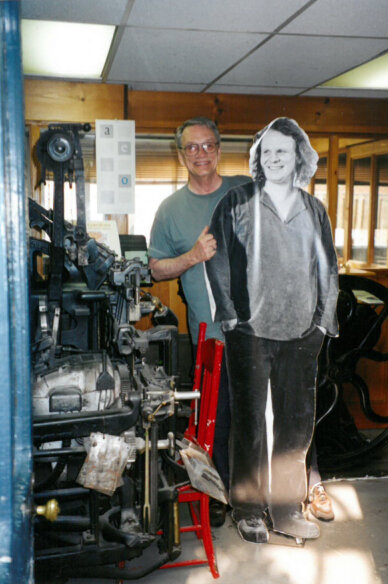

8. This was the last of his many meetings with the great poet bp Nichol at Coach House Press in Toronto. bp was in two dimensions on this occasion, because he had died in 1988, and George is actually embracing a cardboard rendering of Coach House's most illustrious writer. Behind GB and bp the windows give onto bp Nichol Lane, where one will find a Nichol poem carved into the pavement. When it was brand new, Coach House mastermind Stan Bevington opened a big bottle, and soon the poem was filled with champagne. Thus for another generation the wedding of poetry and wine was performed.

9. Early in the 21st century GB fell for a woman who admires animals and birds that are black and white. Jean is nuts for pandas, pelicans, auks and zebras. One day she found out that halfway down the Atlantic coast of Argentina there is a penguin town, a municipality with streets and squares, populated by Magellanic penguins, a million of them. So they jumped onto a cruise ship that was headed for Cape Horn, and joined the crowd that got off to look at the birds. If you looked any direction but east you saw millions of white plastic bags caught in the windblown bushes of the vast plano. The penguin city had one main law: penguins have the right of way. Jean was having a wonderful time hobnobbing with the locals. George, as often happens, fell down, this time on some ancient porous rock, where he acquired a number of bleeding scrapes.

10. It has been his good fortune all through the years to work and play with hotshot painters and other visual artists: Gordon Payne, Roy Kiyooka, Brian Fisher, Charlie Pachter, Pierre Coupey, etc., etc. These are a few of the artists whose works embellish his books and his walls. In 1966 he and Greg Curnoe started their whizbang friendship. They argued in front of neato audiences, started magazines and galleries, sat on colourful chairs and drank black coffee all through the night, and even put a long mural in the arrivals tunnel of the Montreal airport, causing the USAmericans to threaten warfare against its gentle northern neighbour. His happiest moment of the early days was a visit with Greg and his red-haired son to No Haven, the Nihilist Party cottage at Port Stanley. There a more typical woman called the police because one-year-old Owen was walking naked on the beach. Greg and I were fond of such moments.

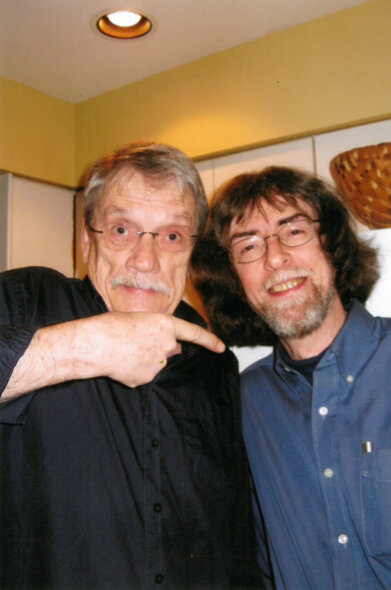

11. His friend Lionel Kearns, seen here with Dan McLeod and Gordon Payne, is now an octogenarian ice hockey player, but when he first knew him he was a rebellious Catholic poet from the West Kootenays. Lionel taught him how to cook a can of ravioli on the manifold of a Chevrolet. When he drove him to the Mexico City airport to fly to Cuba in 1965, the last thing he saw him doing was trying to get the parking police to give him back his license plates. Over the years Lionel keeps finding ways to become a one-poet literary movement. His typewriter concrete poem "The Birth of God" has been presented as a greeting card, a tee shirt, a rubber stamp, an avant-garde musical movie and a mustard pickle.

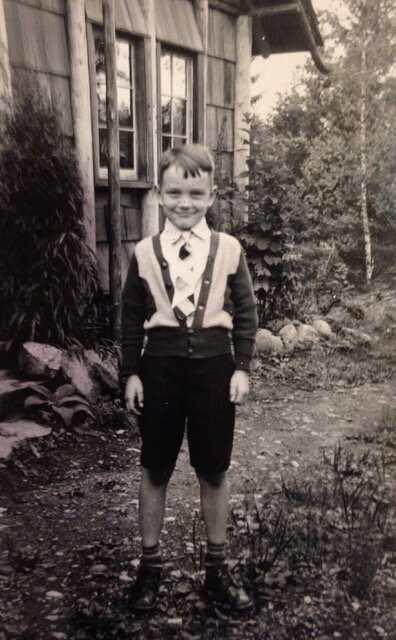

12. He went to the bayou with Roy Miki and Nicole Brossard. He got to watch Roy eat and Nicole smoke. Shortly after lunch one day, he saw Roy eat one hundred crayfish washed down with Jax beer. In Lafayette Roy had a hard time following what the Cajun people were saying in English, and Nicole had a hard time figuring out what the Cajun people were saying in French. But when we got to the big old hall in which people were sawing fiddles and squeezing accordions the language of love had them both stomping the floor.

13. Sheila Watson always maintained that when he came to visit her in Edmonton, he was wearing a black leather suit. Well, maybe in his dream he was, or in her fantasy he was. But her greatest invention was the novel The Double Hook. The first time he tried reading it, he threw it at the wall. The tenth time he tried, he typed the whole thing out. He read the whole thing out loud. He composed a film script of it. He read it in French, and that wasn't fast. He taught it at several universities. One night in NDG he saw Buffy Glassco in a black leather suit, and vowed never to do that.

14. We don't know how many years ago he first met Spider Robinson at some literary do in Red Deer. We all sat in the bar, drinking beer and eating hamburgers and fries out of little baskets, but Spider doesn't eat much or often, and that's why he is six feet tall and weighs about ninety pounds. His lovely wife Jeanne had probably done this a thousand times: "Eat, Spider. Take a bite." But how does a person put bar food into a mouth out of which words, often elaborate puns, are streaming? He would meet Spider , but not often enough, in books and on islands. He thinks of his skinny friend as Callahan's Cutie. He always remembers that night in Red Deer, when he acquired a book with this written in ink on the title page: "We've got to start meeting this way."

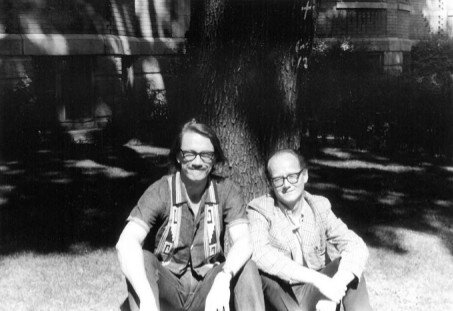

15. Writers and other people are regularly asked to name the most influential teacher they ever had. For him, it was Warren Tallman, the only professor at UBC who had ever read anything by Robert Duncan and Robert Creeley. He was never officially in one of Warren's classes, but he was in Warren's basement, with his friends, listening to Duncan's endless lectures. With Warren's two kids jumping up and down beside him he drove to Oakland to get a box of Crispy Critters. In this photo he and Warren are in front of the former's Montreal apartment, where they have been watching the moon shot on his eleven-inch TV. Warren Tallman was his example as an essay-writer.

16. Note the colours this gent is wearing. He became a Boston Red Sox fan when he was ten years old, listening to them lose the World Series on his Uncle Llew's big radio. During that week he learned to follow the non-winners, as he did in the other league a year later with the Dodgers, as he would all his life steer clear of the best-sellers list and the top hits list. In this way, you could say, he was led to Giuseppi Logan instead of Wayne Shorter, Gilbert Sorrentino instead of Thomas Pynchon, Betty Carter instead of Whitney Houston. He didn't actually eat one of those baseballs, but his dog did.

17. His daughter the fiction writer took this photograph in Courtenay, where her mother had been a girl. Really, you are not likely to find the box scores in the Courtenay paper. You won't even find them in the Vancouver papers. In early August their sports pages are dedicated to ice hockey. He wishes that he lived in a big city with a sports section that would keep his attention for an hour, but he will not cross that line to get one. One of his grandmothers and one of his grandfathers crossed the line to live in Canada, but neither of them ever lived in a city with decent box scores. In any case, he's glad they came up here.

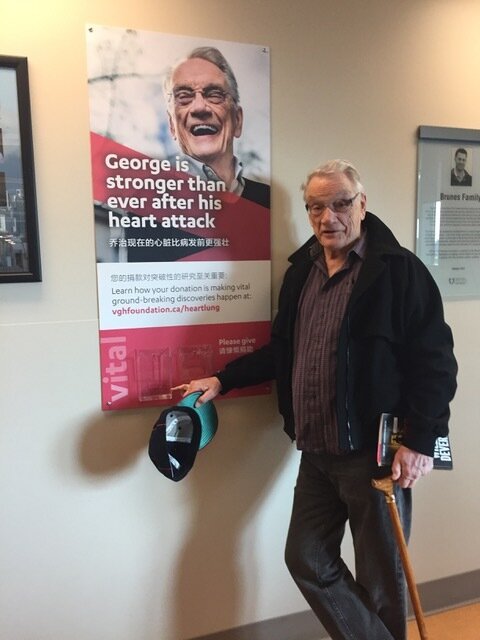

18. He had it when he was eighty something, but it wasn't a heart attack. Everyone gets one of those. It was what they call a cardiac arrest. He had it on the sidewalk in front of his local library. The Vancouver General Hospital and the UBC hospital put up these posters all over their walls and elevator doors, and billboards about the same thing appeared all up and down the block. He had a long sleep with hoses down his throat and missed the ball scores for a few weeks.

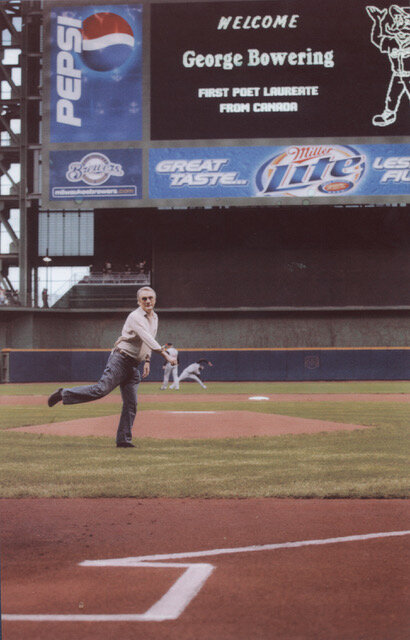

19. He has been asked to throw out the first pitch in quite a few parks in quite a few leagues, but this was his only appearance in the Show. The stadium was Milwaukee's Miller Park, his catcher was Damian Miller, and his grandmother's family name was Miller. What could possibly go wrong? The pitch, a forty mile an hour fastball, caught the outside corner thigh-high for a strike. What the crowd and his teammates did not know was that GB was as sick as a dog, that he had thrown up seven times in seven places that day, including into the river next to Lorine Niedecker's house. But now, on his way back to his seat at the left field foul pole, he stopped for a bratwurst, this being Milwaukee and all. Then he threw it up.

20. When he first saw that Japanese cartoon style, he didn't like it at all. Same thing with Hello Kitty. Now, for some reason, his house is full of Hello Kitty stuff––backpacks, sticker albums, coin banks, notebooks, Pez dispensers. People give him Hello Kitty things. As for the guitar. He doesnt know where your fingers go, but he has played electric guitar a few times with the notorious Nihilist Spasm Band, and once (as illustrated) at the Vancouver race track (don't ask). In the small likelihood that you are interested, that cap is worn by the Salt Lake Bees.

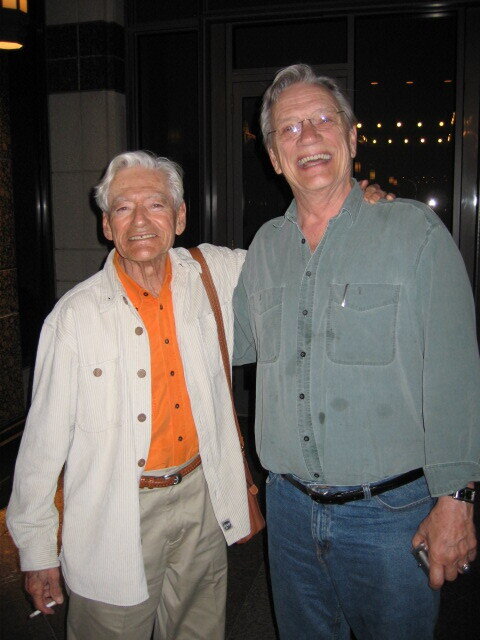

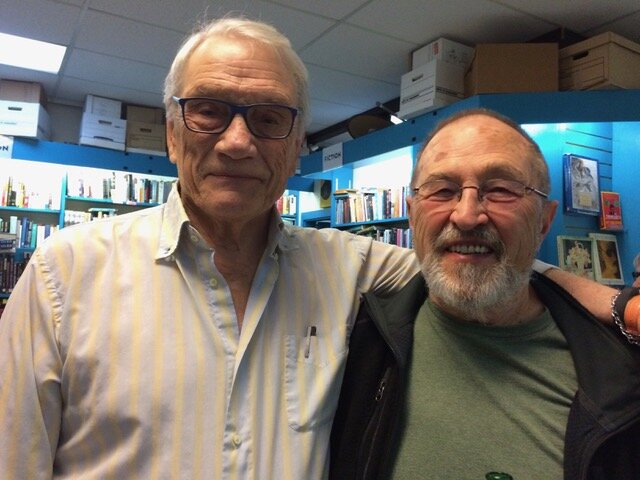

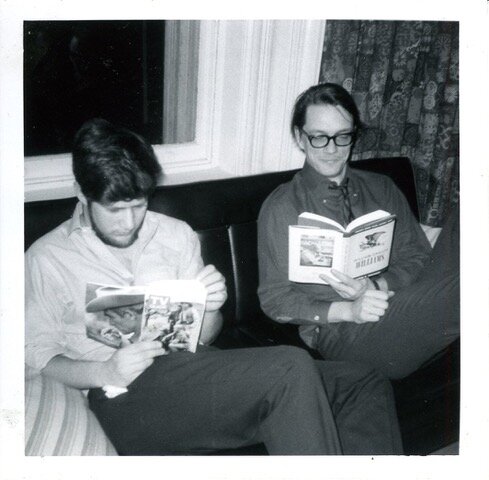

21. GB and Fred Wah met at the University of British Columbia, where one was a literature student and the other studied in the music department. One was from the Okanagan Valley and one was from the Kootenay Valley. One played tuba in his school band, and the other played trumpet. One became an editor of the trailblazing poetry newsletter Tish, and so did the other. One taught for a while at the University of Calgary, and so did the other. One became a regular author with Coach House Press and Talonbooks, and so did the other. One received the Governor-General's award in poetry, and the other did too. One was named Canadian poet laureate and so was the other. One was adopted into the Order of Canada, and so was the other one. One watches basketball games and the other watches hockey games. Well . . . .

22. His parents were good baseball players and poor photographers. This picture was snapped in Peachland, a village for whom his father played first base and led the team in singles. Later in his ballplaying life he liked to claim that his speed afoot made him a blur on the basepaths, but there are witnesses who will not concede. Peachland was a wonderful lakeside town to spend your first four years in. Now it has been engulfed by the voracious developers and real estate villains of Kelowna. Nowadays GB still has a ball glove and bat and a bowl full of baseballs, but he can not stand so effortlessly as this little kid.

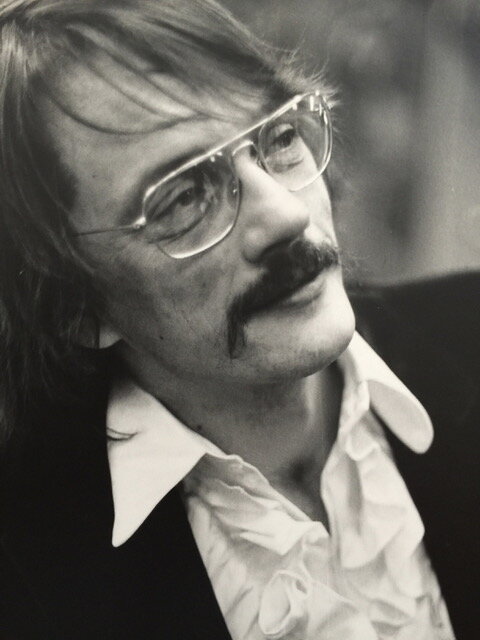

23. Because of his vanity, GB really likes this photo. It was taken in 1970 at McGill University in Montreal by his friend Lynn Spink, who can make the homeliest poet look good. He is wearing his green velvet suit and ruffled shirt, and has removed his black crisscross necktie, because it is time to relax. For the last three-quarters of an hour he has been part of Peter Huse's symphonic thesis for orchestra, featuring a mezzo-soprano and a poet. The great Phyllis Mailing was the singer, and GB spoke Huse's poems. GB has entered into a lot of collaborations with dancers, musicians, painters, poets, novelists and actors, but this was, he says, the most glamorous collaboration he has ever done, and they weren't even his poems.

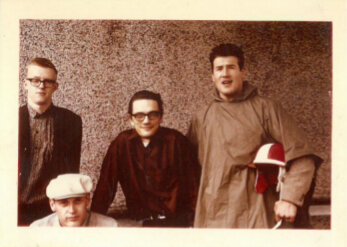

24. Some of them were in Oliver to visit the Rattlesnake Press, the forerunner of Frank Davey's Massassauga Editions and printer of the first Tish book. That's GB in the understated hat. Frank Davey reading a poem, Bob Hogg, and Red Lane. No one knows who the fifth guy is. He and Red were driving around boosting Pepsi machines. The 1947 Pontiac belonged to GB. The TR4 was Frank's.

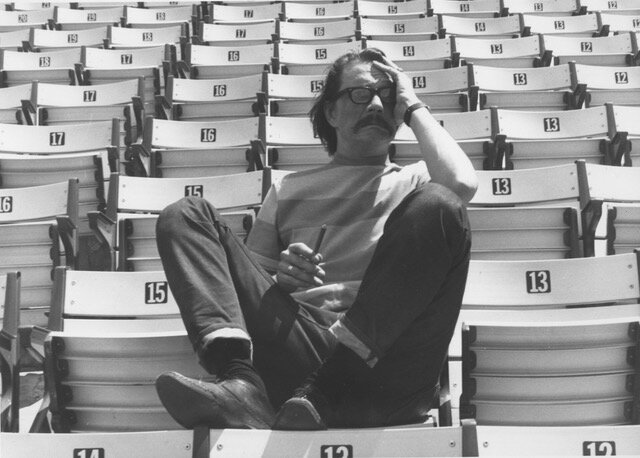

25. The Expos arrived in Montreal shortly after he did. As sports editor of the local alternative paper, he was often in the all-aluminum Jarry Park, which was never as empty as it appears in this mocked-up photo. One day every kid in the place was given a wooden miniature bat. It got really noisy in that aluminum park.

26. The poets are lined up in alphabetical order, just like their books in the university library. Which one would you expect to have stains on his shirt? Which one would you expect to be holding a cigarette? They first met in San Francisco in 1961, when GB was invited to dinner at RB's home. There was a splendid seafood dinner, and though GB never ate anything that came from the ocean, he ate his way through everything on his plate. This was San Francisco and poetry.

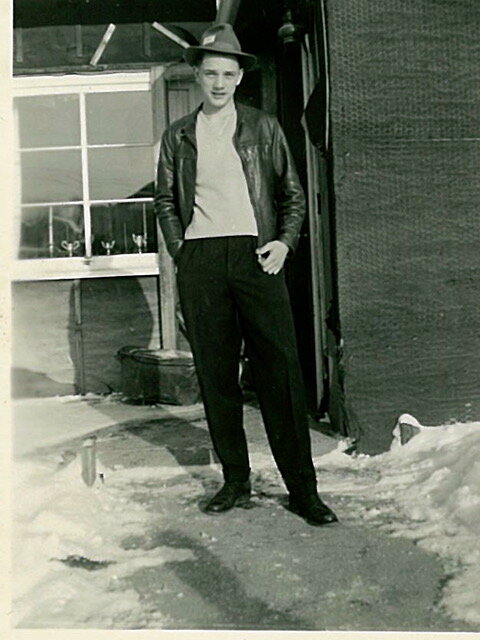

27. See the trophies in the window? His parents were always winning things at bridge or badminton or bowling. He was a teenaged sports reporter, covering baseball and basketball. The Bowerings liked their family initial. See that little card stuck into his hat band? It read PRESS. He had plenty of those cards printed at the Chronicle. One day his little brothers found his pile of cards and gave them out to everyone that passed the house.

28. A lot of photos get taken in front of this big painting by Brian Fisher. In addition to being a genius painter with a taste for geometrical conundrums, he was the catcher for the Granville Grange Zephyrs of the Kosmic League all through the 1970s. About three games into the inaugural season, they got to talking on the bench. GB told him that Brian Fisher was also the name of a really interesting painter. "I'm him," he replied. "I'm the shortstop George Bowering," he said. "I might have heard of you," was the rejoinder.

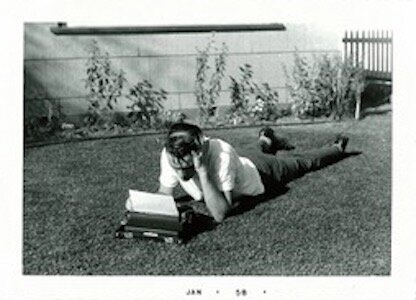

29. He was nuts about his father's portable typewriter. You took the top off and left the typewriter in the bottom, lit a cigarette, and started pecking away. When he was in the air force he borrowed Red Lane's typewriter to write his column in the airbase newspaper. When he came back home he used his father's machine to bang out stories about the Oliver OBC's ballgames. He was going to be a reporter. He wanted to cover all sports for the St. Louis Post-Dispatch.

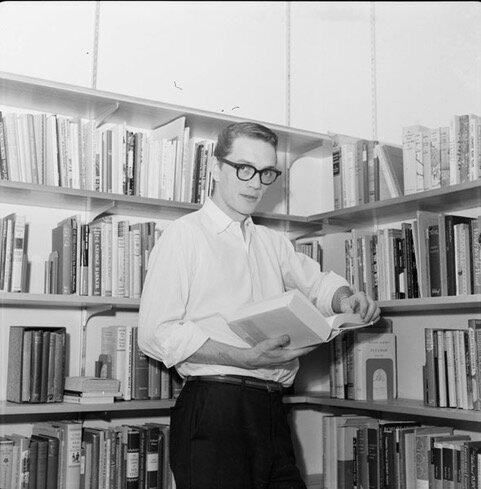

30. In the fall of 1963, he started his first full-time teaching job for $5200 a year at the University of Alberta at Calgary, which would become the University of Calgary. He had, he figured, been dropped among hayseeds who had never heard of Charles Olson. After about a month he was invited to come down and spend a week being visiting poet at the University of Arizona. They told him that he was following Robert Duncan at the post. I am a big deal, just as I always expected, he thought. They put him up in a little suite at the Ruth Stephan Poetry Center. The bathroom was home to the first cockroaches he had ever seen, and he would never see such big ones again.

31. Victor Coleman should have been in this picture, but he took it. These people are outside the main door of Coach House Press, and it is probably 1970. From left to right we have GB, Fred Wah, Daphne Marlatt, Sarah Sheard, Stan Bevington, Michael Ondaatje in the dark doorway, Clifford James. Frank Davey, Nelson Adams, bp Nichol and Ellie Nichol.

32. He was a Brooklyn poet before he ever wrote any poetry. He and Carl Furillo and Jack Robinson and Peewee Reese. The second famous poet he ever met was Marianne Moore, and if she had a higher exit velocity than he, he could think of better names for automobiles. He eventually saw a baseball game in Los Angeles, but then he hightailed it out of town. He does not buy one of those Brooklyn ball caps because they are just made for the market.

33. He sat on the Westmount couch with his friend the poet, reading this and that. His friend the poet and future novelist was into, as they said in 1968, westerns, dog tags from living dogs and Wallace Stevens. He, on the other hand, was into westerns, his two living dogs and William Carlos Williams. They both left the University of Western Ontario without finishing.