The First Episode: Poetry of the Past — the Future, Part I

“The history of all hitherto existing society is the history of class struggles.” [1] Thus begins the first chapter on “Bourgeois and Proletarians” in Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels’s Communist Manifesto written in 1847 at the behest of Communist League and published just weeks before the start of the February Revolution in France. “The French version first appeared in Paris shortly before the June insurrection of 1848,” they add in a later preface. And what began in France in February quickly spread across the whole of Europe in a wave of democratic revolutions known as the “Spring of Nations” after the half-century long winter of reaction that had followed the defeat of Napoleon Bonaparte and the republican tradition of 1789. Germany, Italy, Austria, and Hungary all experienced major revolutionary crises in the spring of 1848 against the bloated and already half-compromised remnants of the ancien régime. It was not only the bourgeoisie — the traditional liberals and republicans, the old heroes of the Third Estate of 1789 — but a new class of urban industrial workers, and a subaltern of lumpenized masses, recent peasants seeking refuge from the crumbling patriarchy of the exhausted land holding, who participated in the political struggle that came with the civilizational crisis known then as the “Social Question.” With the unforeseen rise of the proletariat upon the empty stage of world-history, with the supreme and final flourishing of free and propertyless labor, the age of social revolution — total cosmic transformation — begins. And so it is written, in the “Preamble” to the Manifesto, with the far-reaching voice of a modern delphic oracle:

A spectre is haunting Europe — the spectre of communism. All the powers of old Europe have entered into a holy alliance to exorcise this spectre: Pope and Tsar, Metternich and Guizot, French Radicals and German police-spies.

And again, further on:

Modern bourgeois society, with its relations of production, of exchange and of property, a society that has conjured up such gigantic means of production and of exchange, is like the sorcerer who is no longer able to control the powers of the nether world whom he has called up by his spells. … The conditions of bourgeois society are too narrow to comprise the wealth created by them.

As late as 1846 the coming catastrophe of bourgeois conscience was something that few were anticipating; even the quintessential poet and critic of modernity, Charles Baudelaire — hardly an advocate of respectable manners — began his review of the Salon of that year with a daring dedication, “To the Bourgeois”:

You are the majority — in number and intelligence; therefore you are the force — which is justice.

… The aristocrats of thought, the distributors of praise and blame, the monopolists of the things of the mind, have told you that you have no right to feel and to enjoy — they are Pharisees.

… You have combined together, you have formed companies and raised loans in order to realize the idea of the future in all its varied forms — political, industrial, and artistic.

… For to allow oneself to be outstripped in art and in politics is to commit suicide; and for a majority to commit suicide is impossible.

… When you have given to society your knowledge, your industry, your labor, and your money, you claim back your payment in enjoyments of the body, the reason and the imagination.

… And so it is to you, the bourgeois, that this book is naturally dedicated; for any book which is not addressed to the majority — in number and intelligence — is a stupid book. [2]

The protagonist for Baudelaire in 1846 was still the romantic painter Delacroix “because a long time ago — from his very first work, in fact — the majority of the public placed him at the head of the modern school.” This first painting was The Barque of Dante (1822), a suffering vision of the poiesis of Hell — and yet one whose violent, penetrating misery nevertheless projects, in the viewer’s imagination, an indelible image of promised salvation:

To the spiritual restitutio in integrum, which introduces immortality, corresponds a worldly restitution that leads to the eternity of downfall, and the rhythm of this eternally transient worldly existence, transient in its totality, in its spatial but also in its temporal totality, the rhythm of Messianic nature, is happiness. For nature is Messianic by reason of its eternal and total passing away. [3]

The apotheosis of Delacroix came with the July Revolution of 1830 and his painting of Liberty Leading the People (1830), which revealed the tortured souls of the dead as the heroic citizens of Paris, burning in the inferno, as businessmen, students, prostitutes, and beggars who mount the barricade in order to resurrect, by the sacrifice of their beautiful corpses, an undying hope for peace on earth, the pale ghost of the late, universal republic. The Salon of 1846 culminates in a last, triumphal chapter, “On the Heroism of Modern Life” in which Baudelaire asks of this romantic attitude:

Is it not the necessary garb of our suffering age, which wears the symbol of perpetual mourning even upon its thin black shoulders? Note, too, that the dress-coat and the frock-coat not only possess their political beauty, which is an expression of universal equality, but also their poetic beauty, which is an expression of the public soul — an immense cortège of undertaker’s mutes (mutes in love, political mutes, bourgeois mutes … ). We are each of us celebrating some funeral. [4]

The Revolution of 1848 began in February as a devoted memory to unsettled claims of the contrat social. The Great French Revolution of 1789 — the revolt of the Third Estate, of the bourgeoisie and peasantry, against the First and Second Estates of the Church and aristocracy — had borne the revolutionary republic as the supreme vehicle for realizing the fettered freedom of social cooperation. Ever since the Renaissance and the emergence of the first free city-states, the dominating principles of social organization had gradually passed from the idle hands of ancient priests and feudal lords to the productive capacity of countless individuals working independently and in concert. The first right claimed by the revolutionary bourgeoise for the salvation of all of humanity was the right to the property of one’s self, the sacred right to the fruits of one’s labor: the inalienable share of each individual in the wealth of a creative totality.

By the end of the 18th century, the cooperative ideals of Liberté, Egalité, Fraternité that lay at the foundation of modern, bourgeois life could no longer be contained within the narrow confines of subjective intention but, by the appropriative dynamic conferred to the relations of labor and the principle of exchange, strove for realization as objective social principles: not only the basis of a new political order but the first words of humanity in the new language of freedom that had dawned on the world. But the exultant jubilee was not powerful enough to break all-at-once from an antiquated mold, and the celebratory proclamations that were made in the eternal name of the universal republic soon became strained with the violent tenor of guillotines and the daily tribune of executioners’ lists. Facing the threat of feudal reaction and the restoration of a deposed ancien régime, Napoleon Bonaparte made a last effort to save the revolutionary spirit by channeling it into the practical force of the Empire, raising the banner of the radical Jacobin tradition as the magnificent costume of world-conquering freedom. The tragic defeat of Napoleon I and the dismemberment of his Empire did not, however, mean that the ancien régime could return to its old position without making fundamental concessions to the progressive spirit that had been unleashed upon the world.

After an interval occupied by the frustrated attempts of Charles X to resurrect the shattered feudal order, the July Revolution of 1830 replaced the Bourbon king with the duc d’Orléans Louis Philippe, the son of Philippe Égalité — the famous nobleman who had voted for the execution of his cousin, King Louis XVI, as a fervent member of the National Convention in 1793. Louis Philippe I was thus known popularly as the “Regicide King” or “Citizen King,” and his cabinet was known as the July Monarchy after the revolution, which conferred to the sovereign only an alienable right to rule. In February 1848, the population of France exercised its right to dissolve the monarchy and absorb the sovereign power within its own institutions: the Second Republic which was declared on the municipal ground of the Hôtel de Ville of Paris by the romantic poet Alphonse de Lamartine.

As Marx would write in June 1848:

The February revolution was the beautiful revolution, the revolution of universal sympathies, because the contradictions which erupted in it against the monarchy were still undeveloped, and peacefully dormant, because the social struggle which formed their background had only achieved an ephemeral existence, an existence in phrases, in words. The June revolution is the ugly revolution, the nasty revolution, because the phrases have given place to the real thing, because the republic has bared the head of the monster by knocking off the crown which shielded and concealed it. [5]

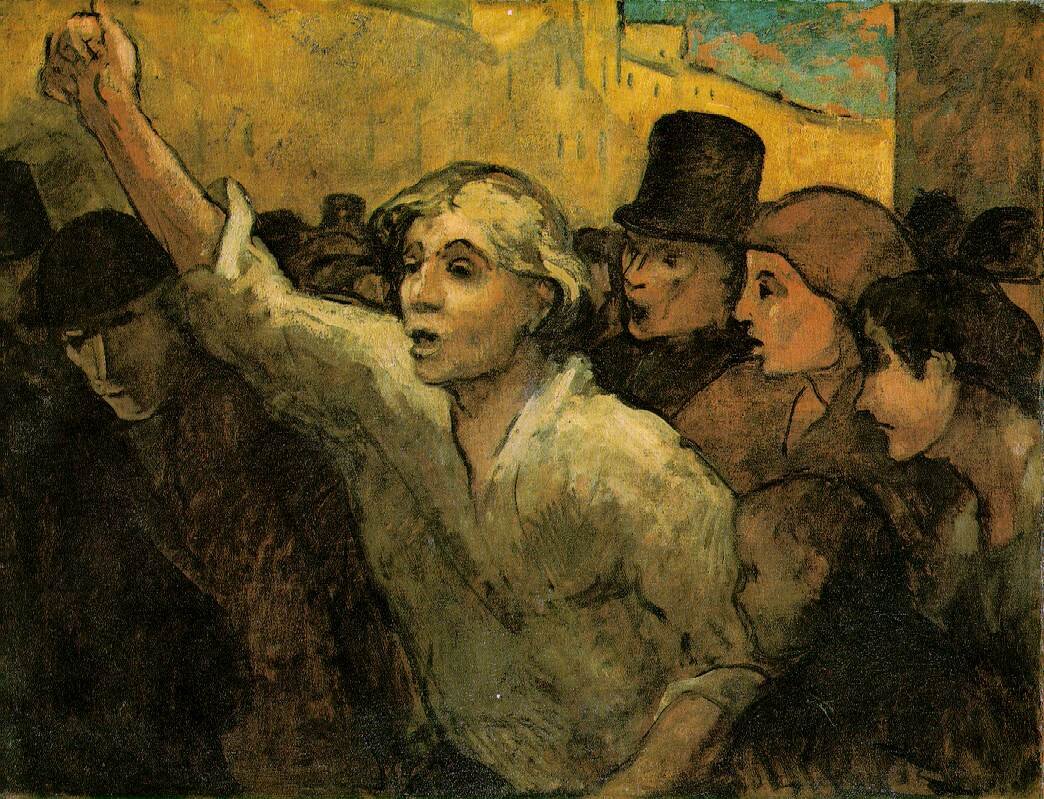

The Second Republic had guaranteed the universal right to work as the fundamental basis for social cooperation, but the economic crisis which preceded the glory of February — the “Hungry Forties,” the first global crisis of overproduction — meant that unemployment was the true face of radical equality: the equal rights of labor to the use of total poverty. The workers of Paris turned against the nightmare of the realized republic, raising the barricade in June against the betrayal of the bourgeois government only to be shot down by the armed citizens of the revolutionary National Guard.

In the high spirits that followed the first flowers of February, many expected that Delacroix would return to the glory days of 1830 so that a new vision of Liberty Leading the People might give form to the freedom that had conquered the world. In the Salon of 1848, the republican critic Théophile Thoré could only look forward to the creation of this future work:

Eugène Delacroix has always been a master of that supreme art that stirs the hearts and minds of a people, turning history into memorable images. His painting deserves the radiant place it has on the cupolas and ceilings of our monuments. … It is said that he has just begun an Equality leading the people; for our recent revolution is the true sister of that national one to which he paid homage eighteen years ago. This time, the entire population made a contribution, and the spoils of victory will be shared equally among them. One can only hope that Delacroix makes haste, and that both paintings will soon be on display, hanging side by side above the head of the President in the National Assembly. [6]

After the massacre of June, no such picture was possible; Delacroix retreated from Paris to his estate at Champrosay where for two years he abandoned the subjects of history painting to devote his energy to renewing the minor tradition of floral still-lifes that began with the memento mori and vanitas of Dutch Golden Age painting. In his letters he writes:“I have undertaken a considerable task and the loss of a single day would set me back badly. The flowers are dying and at the first touch of frost I shall be left without a model.” [7] And again, later on:

I have subordinated the details to the whole as far as possible. I tried to get away from the convention which seems to condemn anyone who paints flowers to reproduce the same vase with the same columns of fantastic draperies to serve as background or provide contrast. I have tried to paint bits of nature as we see them in gardens, only assembling within the same frame and in a fairly probable manner the greatest possible variety of flowers. [8]

Even at this Delacroix proved unsuccessful, producing only a few second-rate canvases, although the studies for these were themselves full of the wonder and life that the finished products so severely lacked. Finally, the only portent vision he could manage of the revolution of 1848 came later in the forest of Senart, a real parable of the struggle between spider and fly:

I saw the two of them coming, the fly on its back and giving him furious blows; after a short resistance the spider expired under these attacks; the fly, after having sucked it, undertook the labor of dragging it off somewhere, doing so with a vivacity and a fury that were incredible. The fly dragged it backward across grasses and other obstacles. I looked on with a certain emotion at this Homeric little duel. I was Jupiter contemplating the fight of this Achilles and this Hector. It may be noted that there was distributive justice in the victory of the fly over the spider; it was the contrary of what has been observed for so long a time. That fly was black, very long, and with red marks on the body. [8]

Thus Equality leading the people...

* * *

Next week I will return to the perspective of Baudelaire after the lessons of June as well as Marx and The Eighteenth Brumaire. Then Courbet's pictorial realism, which springs from the loss of the romantic ideal and paves the way for Manet and the Impressionists. And in the distance, the Commune of 1871… //

Eugène Delacroix, Study forJacob Wrestling with the Angel, 1850. From: Louvre.

Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, Portrait of Monsieur Bertin, 1832. From: Wikipedia.

Eugène Delacroix, The Barque of Dante, 1822. From: Wikipedia.

Eugène Delacroix, Liberty Leading the People, 1830. From: Wikipedia.

Jacques-Louis David, Oath of the Horatii, 1784. From: Wikipedia.

Jacques-Louis David, Napoleon Crossing the Alps, 1802. From: Wikipedia.

Henri Felix Emmanuel Philippoteaux, Lamartine, before the Hôtel de Ville, Paris, rejects the Red Flag, February 25, 1848. From: Wikipedia.

Honoré Daumier, The Uprising, 1848. From: Wikipedia.

Eugène Delacroix, Bouquet of Flowers, 1849. From: Louvre.

Ernest Meissonier, The Barricade, Rue de la Mortellerie, June 1848, 1850. From: Wikipedia.

[1] Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, Manifesto of the Communist Party, in Marx/Engels Selected Works, vol. 1, (Moscow: Progress Publishers, 1969) 98-137. From: marxists.org

[2] Charles Baudelaire, The Salon of 1846 in Art in Paris: 1845-1862, (New York: Phaidon, 1965), 41-43.

[3] Walter Benjamin, “Theological-Political Fragment” in Selected Writings, vol. 2, (Cambridge: Harvard, 2004), 305-306.

[4] Baudelaire, 116-120.

[5] Quoted in Karl Marx, The Class Struggles in France, 1848-1850 in Selected Works, vol. 1, (Moscow: Progress Publishers, 1969). From: marxists.org

[6] Théophile Thoré, Salon of 1848 in Art in Theory, 1815-1900, ed. Charles Harrison et al., (Blackwell Publishing: 1998), 179-182.

[7] Eugène Delacroix, “Letter to J.-B. Pierret 29 September 1848,” in Selected Letters 1813-1863, (Boston: Artworks, 2001), 286.

[8] Delacroix, “Letter to Constant Dutilleux 6 February 1849,” in Selected Letters, 287.

[9] Quoted in T.J. Clark, The Absolute Bourgeois: Artists and Politics in France 1848-1851, (University of California: 1999), 137.