The Sad Lament of the Brave Review

What does it mean to paint? What kind of world does it make? The new paintings of Julian Schnabel, shown by Pace Gallery in New York, are incursions into this metaphysical realm, the cosmos of the painterly image. The Sad Lament of the Brave, Let the Wind Speak and Other Paintings presents seven monumental paintings and four minor ones on pink and purple supports — tarps from a market in Mexico. And while traces of this former use appear on the fabric, even their seams dividing the canvas, these paintings by Schnabel bear a closer relation to the tradition of murals in Mexican painting.

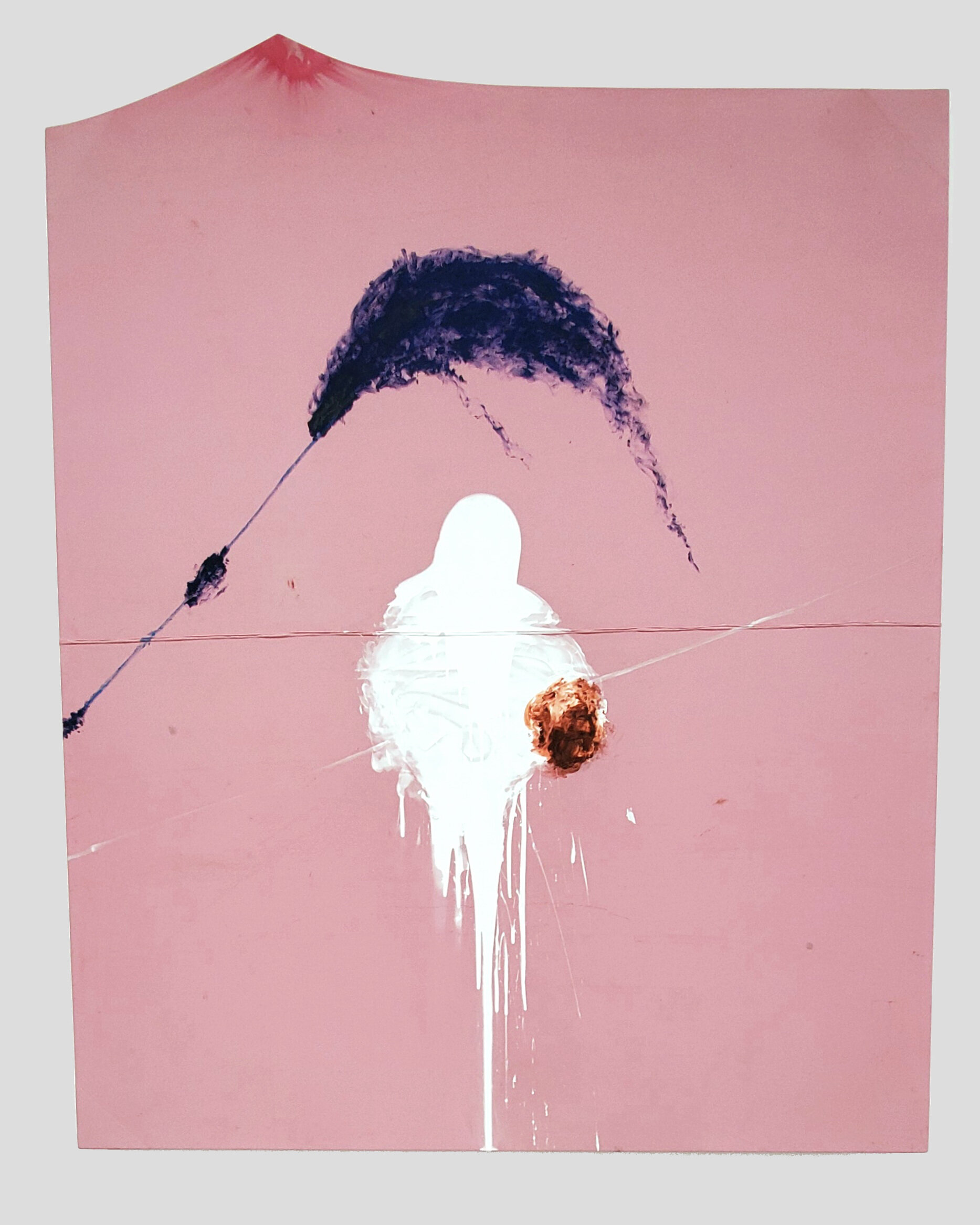

The curved edges of the massive panels in the main room of the gallery send them over and above your head, enveloping the space around you as if they followed the bending lines of an imaginary vaulted ceiling. Thus certain paintings reach a peak marked in bursting red, a critical point where space would fold and pinch as walls and ceiling met. In San Miguel de Allende, at a former convent turned art school, there is a great unfinished work by the muralist David Alfaro Siqueiros, where the lines of perspective composing his sequence of images project into the confines of cavernous stone. A small mock-up of radiating metal hoops shows how Siqueiros sought to transport this architectural space by using the cascading form of its shape to open new vistas onto a painterly world; the cloistering walls of the convent obliterate and give way to an intangible image projected from the mind of the artist. In the works of Schnabel’s Sad Lament, a thick gesso acts to tie the concrete to the imagined, adding to the tactility of the paintings while also creating a presence that inhabits the frame. The patinated color of these pink and purple tarps — spangled with small scuffs and worn marks, little holes and dents — produces an entire atmosphere in which painterly forms are situated. A subtle Surrealism appears: the deep indigo purple and sun-washed pink of Schnabel’s pictures recall the night scenes of Rufino Tamayo and the colorful walls of his watermelon paintings — that mysterious significance which collects on the surface of Tamayo’s dreamlike visions. There is also something of Roberto Matta or Yves Tanguy in the curving movement of the shapes that Schnabel has painted, some like prairie grass blown by the wind or slowly writhing like amoebic forms, drifting like masses in an infinite cosmos, falling like pigeon shit on an abandoned car.

View of The Sad Lament of the Brave, Let the Wind Speak and Other Paintings. Courtesy of the author.

David Alfaro Siqueiros, Vida y obra del genarlísimo Don Ignacio Allende, 1948. Noticias con valor.

What is the lament composed by these works? What is it that the wind wants to say — Strung to the tear without apparent purpose? Perhaps that painting survives in a fugitive state, that it is tethered to existence by a fragile thread. In these new pictures by Julian Schnabel, we see the present state of painting: abandoned like unfortunate refuse, making do with what it has, left to its own devices, to elaborate what still remains within it. Real images are scarce these days; a relentless tide of visual matter has left us inundated with the hollow signs of branding and graphic design and the endless stream of formless content that somehow passes now for contemporary culture. What a dismal world in which to be an artist — where each image is a tenuous fiction cast out into a violent current. And yet something may outlast this tempest; these tarps may carry their load. //

Rufina Tamayo, La gran galaxia, 1978. Latin American Art.